Is there such a thing as Islamic Art and Architecture?

What makes something Islamic?

Is it the architect or artist who creates the form, or is it the bricklayer who places the bricks in a certain fashion or is it the land or time in which it is created? Or can such a rich and diverse art form be attributed (in its multiplicity) to the One God (the Singular)?

Some would argue that there is no such thing as ‘Islamic Art’, that no faith can attribute to itself the credit for the achievements of its people, especially those that are outwardly physical in the world of art, architecture, music or literature. That the Taj Mahal cannot be considered ‘Islamic’, nor the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in Isfahan, nor the Ummayad Mosque in Damascus. It can be argued and asked, “how can a creed, a philosophy, a set of beliefs that dictate human ethics and behaviour become present and own the way a stone is carved, or how a page of calligraphy is illuminated, or how the harmoniously a space is designed?”. In Christianity for example, the label of ‘Christian Art’ strictly means ‘sacred art with themes and imagery from Christianity’, the rich architecture of the Vatican, Rome or Florence in Italy is not considered ‘Christian’, the sacred text within the old or new testaments are not able to claim credit for what was constructed.

Conversely, an argument can be made that certain human creations could not have come to existence without the love drawn from the conviction of no god but that one God, the same God that inspires, the God that comes to be manifested in our creations, the God that is found in the halls and courts of the palace in Granada, the God that emits His light through crystal lamps found in Mamluk architecture in Cairo, the God that is buried deeply and on the surface of Iznik tiles in Ottoman architecture, the very same God that is plastered over the domes of Safavid mosques in Iran. It can be argued, and this is the position I take, that the Truth of God is what Muslims have etched, chiselled, stained, carved, painted, glazed and then raised in their creations in this world. That what the hands of one man did in Istanbul have not be repeated by a hundred thousand others who deny the Truth of God.

So, what do we mean by ‘Islamic Art’?

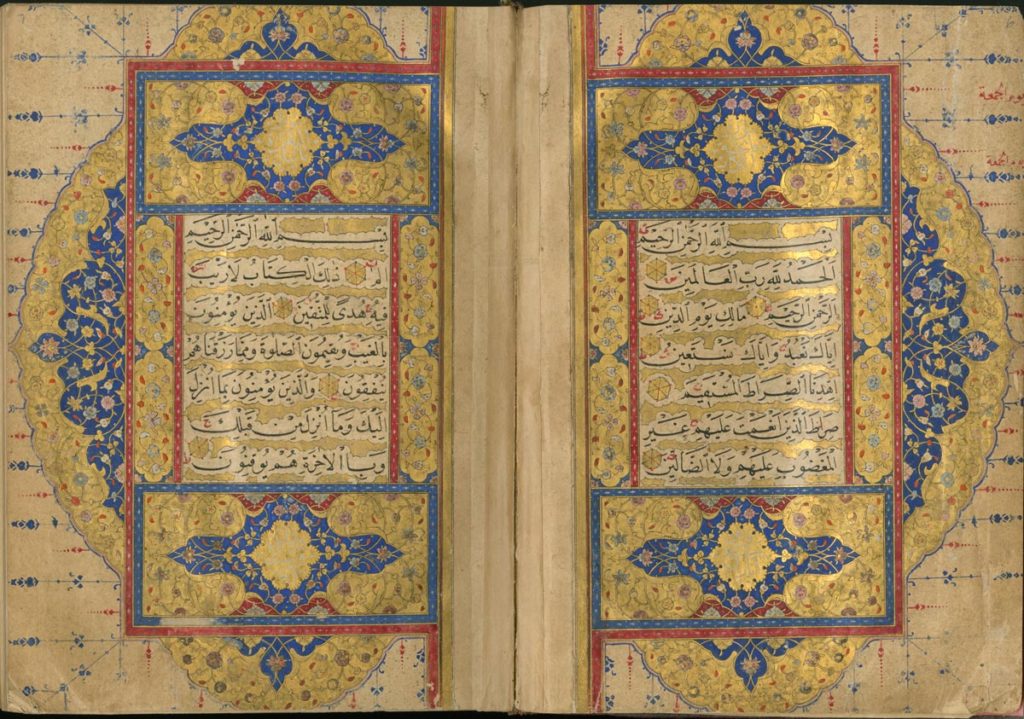

If the term ‘Islamic Art’ can only be applied to art that has elements of sacred text, such as illuminated manuscripts with Arabic calligraphy or beautifully decorated versions of the Quran, then we are doing Islam and its impact on the creative world a great disservice.

The creation of art that is rooted in the remembrance, glorification and demonstration of our love for the one God, Allah swt, or his beloved messenger, Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and the sacred words within the Quran should qualify all and any art to be undoubtably ‘Islamic’. Inspiration from and adherence to the message of God is obedience, it is submission, it is demonstrable practise of Islam.

The resultant art form can take many forms, whether it is written, recited, carved, or constructed. The decision of the artist to use a particular style, or to limit oneself (for example Islam prohibits aniconism, the representation of the human form in art), has created art that would otherwise have never been developed.

“Aniconism unleashed the passionate Arabic genius for abstraction in symmetrical, meditative geometry. This geometry organized the foundations of their architecture and ornament. Abstract pattern also expresses a basic tenet of Islam: “Instead of ensnaring the mind and leading it into some imaginary world it dissolved mental fixations and detached consciousness from its inward idols.”

Al-Tahwid, the doctrine of unity, also gave birth to the art of Islamic pattern, expressed through symmetry that appears to be infinite.

The rise and rapid expansion of Islam delivered revelation to the world that was heavily soaked in the concepts of beauty and love. Unlike other organised religions or philosophies, Islam was multi-dimensional in what it asked of man and what it offered. To a reductionist, Islam is nothing more than a creed that demands obedience and submission, and perhaps many Muslims may see their own faith as this. To the artists who submit their heart to Allah, there is a question that is often asked, the beauty that I find in my God, in my beloved Prophet, in my sacred Quran, in this beautiful world – what is the purpose behind it all? And what inspires man to express his love for Him through art, when all that is required is plain submission and obedience?

“God is beautiful, and He loves beauty” – Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)

My submission to accepting the truth and oneness of God came not from the glorious Quran, though it did instil in me a fear and respect for our Creator, instead it was found under the decked ceilings of the mosques and palaces in Spain, Turkey and then Iran, where the gold and turquoise, the stone and stucco, the marble and wood, the carved and the polished, the calligraphic and the arabesque spoke to me and invited me to submit. These creations did not wow me as they do to many, they made me inquisitive and so I obliged and enquired, who created this and why? As a child of the European sun, I was raised on rationalism with no exception, what is comprehensible is what we perceive, and what we perceive is all that is existent. If we study Van Gogh and analyse his inspiration, if we gaze at Monet and ask why, and if Romanticism, Idealism and Realism all have within them a cause and movement, must not the work of Islamic art be the same? Where would Islamic geometric patterns, motifs of plants and calligraphy fit in? what movement or ideology did they represent, and where does the work of Muslim artists sit in retrospect?

Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Caravaggio, Da Vinci, Botticelli and many more have created some of the greatest Christian Art Europe has ever seen (and I argue will ever see), yet almost all of these artists today are celebrated not because of their Christian heritage, but in spite of. If Europe has divorced its own cultural heritage from its religious roots, why must not the same practise be applied to the easterly Islamic world the modern mind is asked? This I fear, is the less known force driving the narrative that there is no such thing as ‘Islamic’ art.

I recall entering the Alhambra Palace (Cordoba) in the year 2013 in a very unprepared state. As a Muslim I entered the grounds with a sense of pride, not knowing why or from where this presumptuous pride should arise, but it rose and I wore it nonetheless. Moorish poets described Alhambra as a “pearl set in emeralds”, an allusion to the colour of its stone and the woods around it. The parks within Alhambra is home to nightingales, and filled with the sound of waterfalls, and each segment of this palace was designed with the theme of paradise on earth. What paradise and who’s paradise? In Islamic religious literature, Paradise, or Jannah, encompasses rivers and springs, large trees for shade.

“One day in paradise is considered equal to a thousand years on earth. Palaces are made from bricks of gold, silver, pearls, among other things. Traditions also note the presence of horses and camels of “dazzling whiteness”, along with other creatures. Large trees whose shades are ever deepening, mountains made of musk, between which rivers flow in valleys of pearl and ruby.”

There is nothing ordinary about Granada, or any of the other Muslim cities in Spain. The 800-year rule of Muslims in Spain and Portugal left a flower planted so heavy in its scent of God, and of God’s beauty that 800 years later it has not wilted despite the attempts of man and time. I recall standing in the ‘Court of the Lions’ and feeling a sense of shame and confusion, here I am self-proclaiming to be a heir and descendent of the architects that created this space, and yet, I myself did not understand how or why this place existed. While many saw this court and its lions with plain curiosity and awe, I felt a harmonious and sacred design language speaking to me. I have been to countless cathedrals and European palaces, yet none designated this unique design language that I realised I would have to decipher, because whatever entity, group or human or sacred philosophy produced this was not merely inspired by his own imagination, Alhambra was an attempt to capture God in one place, His attributes, His mercy and His beauty. As a non-practising Muslim at this point, I felt myself tremble that I had found God in one of his forms, and who would now deny me the truth that this architecture was most certainly Islamic. How could it not be?

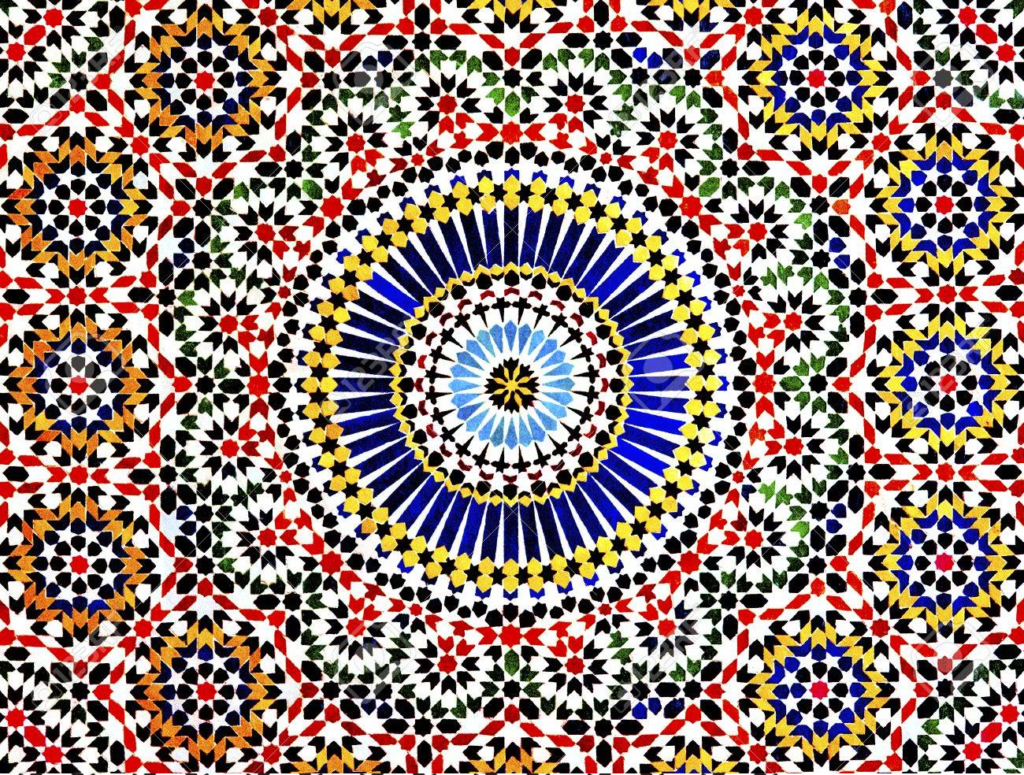

The Alhambra tiles are also remarkable in that they contain nearly all, if not all, of the seventeen mathematically possible wallpaper groups. A wallpaper group is a mathematical classification of a two-dimensional repetitive pattern, based on the symmetries in the pattern. Islamic art generally, exploits symmetries in many of its art forms.

Why do we create?

The Qur’anic term iĥsān. The classic definition of iĥsān comes from the hadith of Gabriel, wherein the Prophet ﷺ describes it as “to worship God as if you see Him, for if you do not see Him, He sees you.” Most simply, the Islamic arts cultivate iĥsān because the patterns on traditional prayer carpets; the geometric designs and calligraphy ornamenting mosques and Islamic homes; as well as the architecture of these homes, mosques, and madrasas help us to worship God as if we “see Him” through these displays of beauty, for “God is Beautiful and loves beauty.” – Oludamini Ogunnaike

Are our attempts to create art and architecture our way to recognise and worship our God? I would position myself and yes absolutely. Are God’s attributes beyond our rational logical understanding? Would this argument then explain why Islamic architecture embeds itself geometrical and symmetrical designs that allude in Sufism to the eternal properties of God? If the ‘nukta’ (dot) is the centre of our creation, is He the nukta? The compass rests its needle in a single space and from it creates a framework, an orbit from which the rest of art, the rest of us are created. What is this ornate world if not inspired from revelation?

The Qur’an repeatedly says “God loves the beautiful-doers (muĥsinīn)”

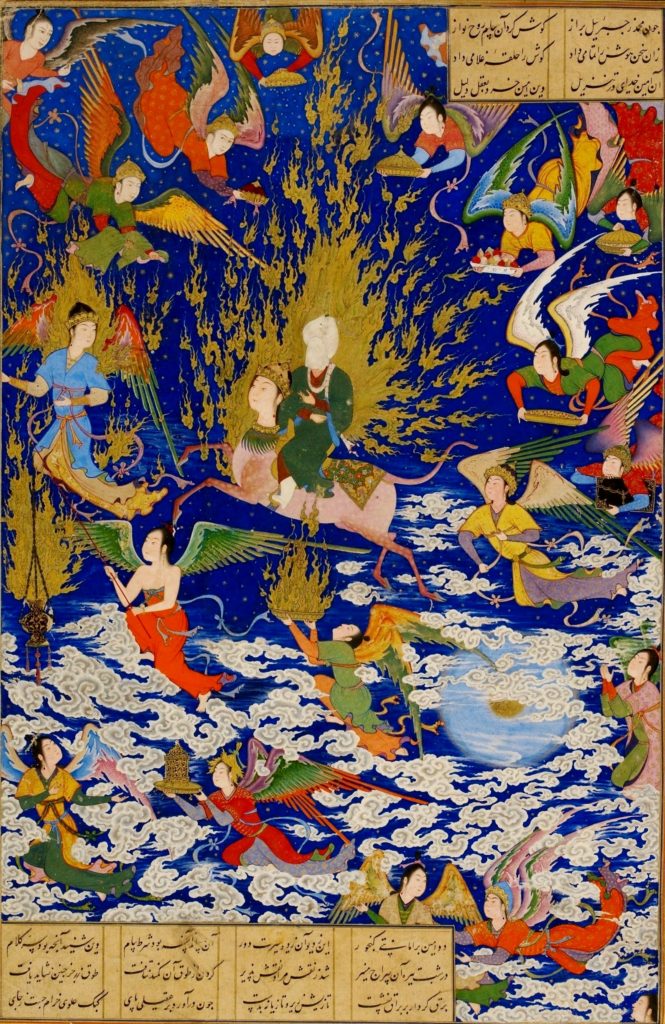

Do we create to please our God? Or is to please our own egos? did the Timurids raise Samarkand as a hub of power and might, or did they raise their eyes at the constellations dotted in revelation and paint what entered their heart? For what else can explain Bukhara or Nishapur, Isfahan or Baghdad?

The Sacred Walls

If Timur was a brute, and if the Ilkhante (the Mongols who became Muslim) were barbarians, if the Safavids were religious zealots, and the Ottomans an imperial menace, how did the sacred Truth instil itself in their creation the way it did not in their European equivalents? Because power and fear cannot force beauty with sacredness and the truth, no grandness can replace the single Truth. The Pharaohs, Romans, Sasanians and even pre- and post-modern European powers have not been able to replicate or create a uniform, yet separate style and forms of art and architecture, that span from one end of the world (Morocco) to the other (Indonesia) that inspire and creative awe at the majesty of God and His word.

For if fear and slavery created Samarkand and Cairo, and one can argue, as was the case with Romans and their adoption of Christianity, what raised the height of beauty and imagination that no Byzantine or Roman, no Italian or Prussian could compete? I would argue, and I welcome the challenge, that any other empire or dynasty in history of mankind has produced, consistently, art and architecture that on a purely artistic level stand side by side with what the Safavids achieved in Persia or what the Mamluks did in Egypt.

The pivotal difference, and this is critical, that in the European experiment with religion, man came close to plastering God on his cathedrals but was not able to pull in his fellow brother to prostrate his head freely once the emperor or monarchy was beheaded. What the Europe ruler created delivered awe and submission to the ruler, not to God. What Islam delivered, and continues to, is beyond the physical and is a portal to the metaphysical. On this we must expand.

To a spectator who visits Iran or modern Turkey, or the city of Old Cairo or the sacred Fes, must first observe the outward beauty of what the Muslim has created, but then he must observe the fervour in the hearts of the worshipper and pilgrim, wealthy or poor. For God is not glued to the ornaments of the walls or ceilings, nor does He sit on the minaret or atop the dome, He is ever present in the brick and the layer of plaster that hang low and high in the Muqarnas. For what was created with the beauty of revelation does not lose its sacredness. If you have ever visited an old and derelict mosque, no matter the physical negligence, the overwhelming feeling of the presence of God can overtake you.

The Vocabulary of Islamic Art

Islam does not prescribe any particular forms of art. It merely restricts the field of expression. Ideology of Islam depends on the fixed and variable principles. Fixed indicate to the main principles of Islam that could not be changed in place and time including the oneness of God, while the variable depends on human vision in different places through time. It’s called the intellectual vision inherited in Islamic art. – Jeanan Shafiq

Islamic belief in Aniconism (the avoidance of images of people and other beings) and the doctrine of unity (al-twahid) has always demanded a rich vocabulary of abstract and geometric forms that translated into the architecture of mosques. Muslims artists have traditionally reiterated these forms in complex decoration that cover the surface of every work of art from large buildings, to rugs, paintings and small sacred objects. This vocabulary of art (with its restrictions placed on Muslim artists) has given the world a style and form in the array of carpets, ceramics, furniture and textiles that has made its presence feel all over the world.

The absence of icons in Islam has not merely a negative but a positive role. By excluding all anthropomorphic images, at least within the religious realm, Islamic art aids man to be entirely himself. Instead of projecting his soul outside himself, he can remain in his ontological centre where he is both the viceregent (khalîfa) and slave (‘abd) of God. Islamic art as a whole aims at creating an ambience which helps man to realize his primordial dignity; it therefore avoids everything that could be an ‘idol’, even in a relative and provisional manner. Nothing must stand between man and the invisible presence of God. Thus, Islamic art creates a void; it eliminates in fact all the turmoil and passionate suggestions of the world, and in their stead creates an order that expresses equilibrium, serenity and peace. – Titus Burckhardt

The Dome

The magnificent dome, the canopy above the earth, the tent that guards the earth and the worshipper, this is a symbol of the heavens, the celestial presentation of the heavenly constellations upon which the glory of Allah is cast. Alongside the minaret, the dome has come to represent Mosques throughout the world. The dome was not a Muslim invention, but it was certainly popularised and spread by the expansion of Islam. The origin of the dome is not clear, but in some estimations the oldest example traces back to Pre-Islamic Persia. Muqarnas too are attributed to Persians, and in some opinions to the Egyptian Mamluk, in any case the spread of Islam saw the development and sharing of design languages to the wider Muslim world. Today one enters a mosque and the instinct is immediately to bend ones neck to gaze up at the inside of the dome, for this is where the sum of the whole meets, this is where the raised hands lead to, for this is where we look to find our Creator, sitting, in the calligraphy, between the lines, infused in the gold and the blacks, in the work and craft of the labourer, the lover, that artist, and that architect who raised this dome as a physical attribute to represent the beauty of our Creator.

The magnificent domes of magnificent mosques are part of this Islamic architecture. It represents the oneness of God, the circle dome sitting on the square base structure of the mosque, representing the unity in multiplicity. It represents the mathematical fusion of a circle and square, because the “celestial” sphere or circle joins with the “earthly crystal of the lower octagon”.

The Selimiye mosque in Edirne was constructed on the orders of the Ottoman Sultan Selim II, who claimed the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) came to him in a dream and asked him to build it there. The architect was Mimar Sinan, who after the completion called it his masterpiece. The Selimiye mosque embodies the spiritual symbols of Islam.

“As soon as you enter Selimiye, you encounter a dome that surrounds you. This huge dome speaks of the oneness of Allah. The five-step windows represent the five pillars of Islam. The giant dome, 32 meters in diameter, marks the 32 “fards” [obligations] of Islam. The platforms of the four muzzins indicate four sects. The six paths of the rear minarets depict the six pillars of faith, while 12 marble columns are interpreted as the 12 fards of prayers” – Ahmet Hacıoğlu

In the year 1550, under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, Sinan was ordered to build a great mosque, the Süleymaniye. This mosque would become iconic in Istanbul and today is considered one of the marvels of Islamic architecture. This mosque however had other elements within its complex, including four colleges, a soup kitchen for the poor, hospital, asylum, bath, caravanserai and a hospice for travellers. The mosque here is more than a place to worship the one God, it is a sanctuary for the needy, it is place to educate the young, a refuge for the traveller and a relief for the sick. All elements of charity central to Islam.

In the design of the Süleymaniye, Sinan tried to achieve the largest possible volume under a single central dome, believing that this structure, based on the circle, is the perfect geometrical figure, representing the perfection of God.

The Minaret

In the thousand cities of Islam stand tall ten thousand minarets. Travellers throughout history have recalled and marvelled at these towers that symbolise mans reach into the heavens as a sign of the glory of Islam. If you have visited Cairo or Istanbul, stand in the old medina and count, or attempt to, the horizon of minarets, the lowest level of paradise on earth. The Selimiye Mosque in Edirne has four pencil shaped minarets, each 83m high, the tallest in the world. These pierce the heavens and represent man’s reach to the heavenly constellations.

The muezzin climbs these minarets to announce and then invite all followers of Islam to come pray to the One true God. What stirs in the heart when a voice from above invites you? Would the minaret have existed if there was no muezzin, no call to prayers?

The Mihrab

The messenger of Allah, Prophet Muhammad pbuh would pray and guide the Ummah from a spot in his mosque in Medina. Omar Ibn Abdil Aziz, in the year 88 Hijria, made it hollow and turned it into what we now call ‘Mihrab’. One can view it as an empty arch that points to the sacred city of Makkah serving an operational function but it can be seen as the symbol of The Divine in the context of the mosque. These mihrabs are associated with sacred focal point of the faith and hence the act of submission in prayer.

Often Mihrabs would incorporate depictions of lamps, flanked by candles and framed within Quranic inscriptions. The lamps that are represented on them are assumed to be mosque lamps, implying connection with prayer. References to the mysticism of Ghazali’s Mishkat al-Anwar (The Niche of Lights) and to the Ayat al-nur (the Light Verse, Quran 24: 35) project a symbolic relationship between these compositions and the Light of God in the mosque. This relationship is based on the occurrence of the Light Verse on numerous actual lamps and on the supposition that flat mihrabs are representations of niche mihrabs in which such lamps are hung.

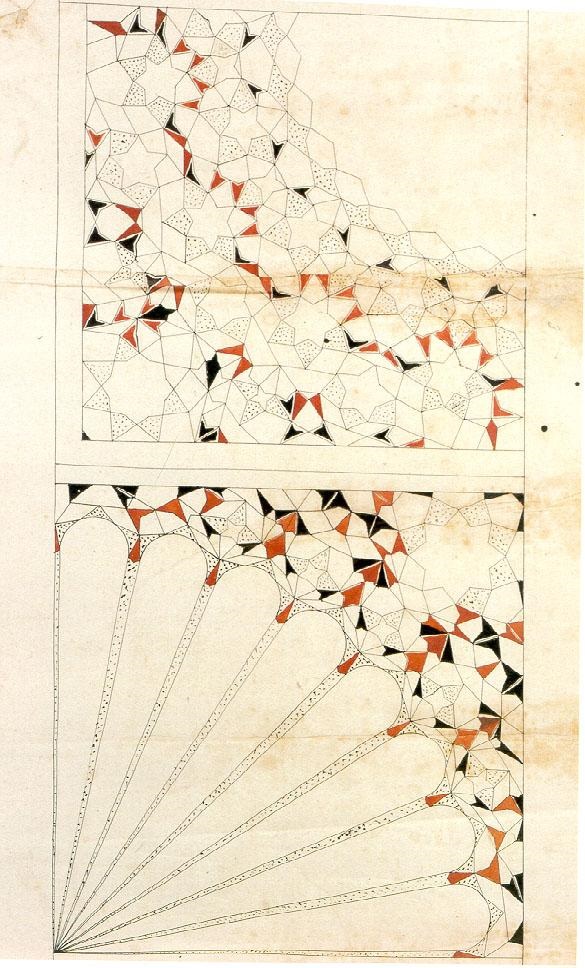

Islamic Geometric Patterns

Keith Critchlow argue that Islamic patterns are created to lead the viewer to an understanding of the underlying reality, rather than being mere decoration, as writers interested only in pattern sometimes imply. The patterns are believed to be the bridge to the spiritual realm, the instrument to purify the mind and the soul.

Principle of Unity

Islamic art is fundamentally derived from tawhīd that is from an assent to or contemplation of divine unity. The essence of al-tawhīd is beyond words; it reveals itself in the Koran by sudden and discontinuous flashes. Striking the plane of visual imagination, these flashes congeal into crystalline forms, and it is these forms in their turn which constitute the essence of Islamic art (Burckhardt, 1967).

Unity is the heart of the Muslim revelation. Just as all genuine Islamic art, whether it’s in Alhambra or Paris Mosque provides the forms through which one can contemplate The Divine.

Unity manifests itself in multiplicity. All the sciences that can properly be called Islamic reveal the unity of nature. One might say that the aim of all the Islamic sciences and, more generally speaking, of all the medieval and ancient cosmological sciences is to show the unity and interrelatedness of all that exists, so that, in contemplating the unity of the cosmos, man may be led to the unity of the divine principle, of which the unity of nature is the image (Hossein 1968).

Unity in Multiplicity

There are two typical forms of the arabesque; one of them is geometrical interlacing made up of a multitude of geometrical stars, the rays of which join into an intricate and endless pattern. It is a most striking symbol of that contemplative state of mind which conceives “unity in multiplicity and multiplicity in unity”

Principle of Eternity

God is eternal. It is an indefinite existence without a start or finish. Islamic ornament is an arrangement in line with the principle of eternity in decoration can be seen here. The stars and hexagon were decorated with vegetal motifs which were placed as if they are continuing in four directions from the centre: upwards, downwards, to the right and to the left.

Principle of Abstraction

According to the essence of this principle, which is also described as “escape from realism”, objects in a work of art are not depicted as they actually look, but they are represented differently after being stylized. The goal of making such a change is not to distort objects and depart from the truth but to apply a different interpretation.

Unity itself alone deserves representation; since it is not to be represented directly, however, it can only be symbolized and at that, only by hints. There is no concrete symbol to stand for unity, however; its true expression is negation, not this, not that. It remains abstract from the point of view of man, who lives in multiplicity.

Principle of Recurrence and Rhythm

Ornament involves many regular shapes placed inside circular forms that are not marked with definite contours but can be recognized when looked at them; these shapes inside the circles then fluently turn into star shaped polygons. As circles decorate the work of art with a rhythmical repetition, different arrangements formed at the connection points also create motifs with more circles and polygons.

Islamic art concentration on geometric patterns draws attention away from the representational world to one of pure forms. The significance from the Islamic standpoint is that, in the effort to trace origins in creation, the direction is not backwards but inwards.

The intuitive mind, or the soul, of an individual seeks sources and reasons for its existence it is led inward and away from the three-dimensional world towards fewer and more comprehensive ideas and principles (Keith Critchlow, 1976).

Islamic Calligraphy

“Read in the name of your Lord Who created; created man from a clinging substance. Read, and your Lord is the most Generous Who taught by the pen; taught man that which he knew not” (al-‘Alaq, 1-5)

Islam arrived in Arabia when reading and writing was a privilege granted to a very few. Our beloved Prophet (upon him be peace and blessings) was an illiterate, as was much of the community around him. Islam changed this all. In the next few decades the Quran was penned to bone, leaf and parchment. In the next few centuries the Islamic world created the first global literary movement, where monasteries and churches in Europe were lucky to have a few copies of the Bible, Baghdad and Damascus, Fes and Granada had streets full of booksellers. The written word was the quintessential mode of preserving tradition, the word of God and the laws of the caliph across the vast Muslim lands. Calligraphy, like other forms of Islamic inspired art and architecture, took paper to recognise, celebrate and share the Truth about God. This movement to put pen to paper to create art was entirely ‘Islamic’. Revelation was directly recorded to paper and beautified, what began as a necessary and practical step in preserving the integrity of Islamic creed, became an art form that left paper and scrolls and leapt onto the walls and ceilings of mosques. What was once written with the minerals of the earth was now carved into the wood and stone in domes, minarets, columns, arches and walls of mosques all over the world (from Morocco to China).

“Arabic calligraphy also provided a basis for decorative forms. Sacred Qu’ranic writing evolved into abstract pattern, enhancing Islamic ornamentation with both visual and spiritual symbolism.”

Today an unaware observer might gaze up at the beautiful Arabic, Persian or Ottoman script in mosques and quickly dismiss the incredible form and styling of words and verses that left the tongue of illiterate Arabs and became, what is in my opinion, the most advanced and sophisticated form of lettering, type and art in any culture and civilisation and history.

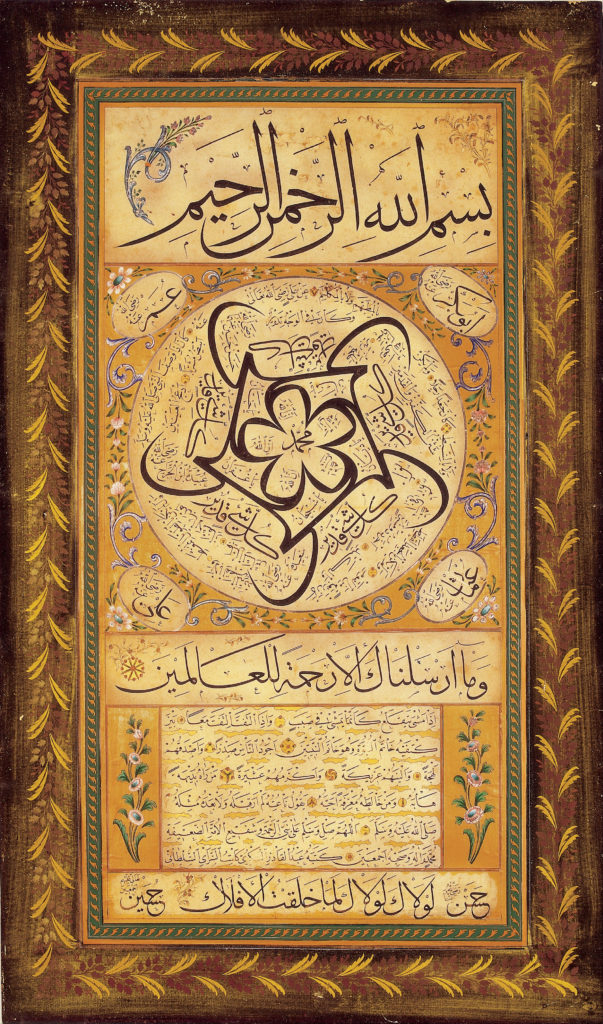

The ban or restriction of imagery in Islamic art also touched the development of Islamic calligraphy. Forms of Islamic calligraphy evolved, especially in the Ottoman period, to fulfil a function similar to that of representative art by means of calligraphic representation, when on paper usually with elaborate frames of Ottoman illumination. These include the name of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), the hilya, or description of his physical appearance, similar treatments of one or more of the names of God in Islam, and the tughra, a calligraphic version of the name of an Ottoman sultan. If you cannot depict the Prophet, you attempt to beautify his name in any form you can.

The Quran

"the decorated pages of a Qur’an can become windows onto the infinite."

The special language and structure of the Quran makes it relatively easy to memorise. The language carries the reciter from word to word, the structure guides from verse to verse, propelled by imagery and picturesque style. The recitation of the Quran is a highly developed art form. It has two generally accepted techniques: a musically beautiful reading, tajwid; and a slow, deliberately simple chant.

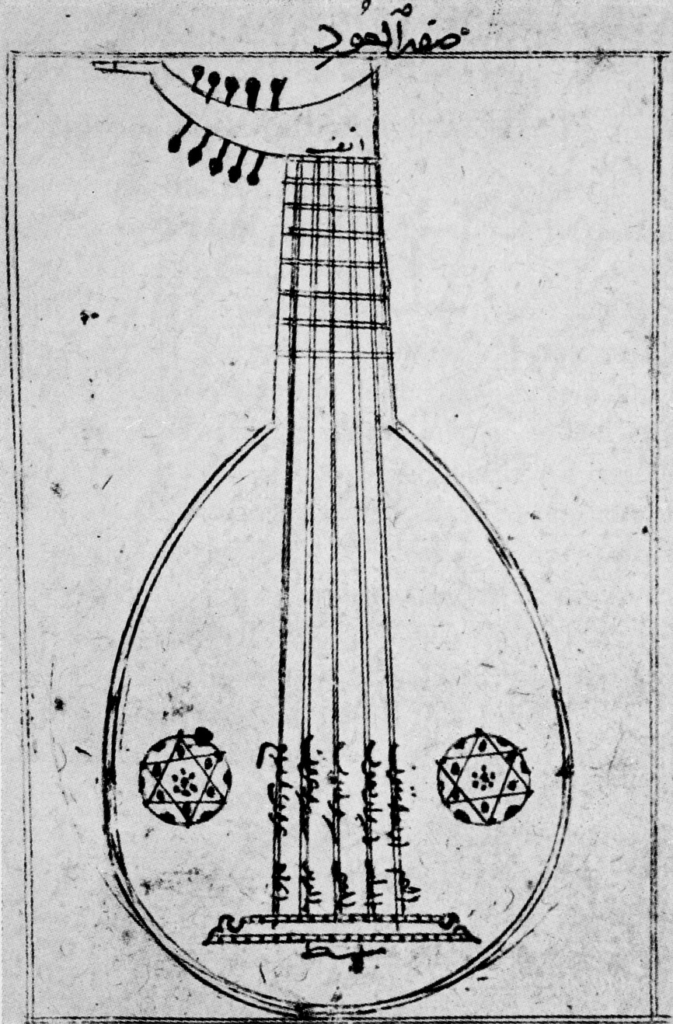

Music

Muslims classified music as a mathematical science, and numerous mathematicians, philosophers and mystics wrote treatises on music. But the most famous work on the theory of music is by Safi al-Din (1294). The ‘classical’ system of music was championed by al-Mawsili (d.850). His student, the master musician Ziryab, introduced this system to Spain in 822. The most outstanding contribution of the Muslim theorists was the development of mensural music, introduced to Europe in the 12th century, before which measured songs was unknown to the west. Equally important was the concept of gloss or adornment of a melody. It was a type of gloss known as tarkib, the striking of a note simultaneously with its fourth or fifth octave, that gave Europe the idea of harmony.

Hilya

Hilya, Arabic for “ornament,” refers to a genre of Ottoman Turkish literature associated with the physical description of Prophet Muhammad pbuh. The concept originated from the shamayil, the study of the Prophets pbuh appearance and character. According to Ottoman belief, reading or possessing an account of Muhammad’s attributes protects one from danger, harm, evil, and sickness. It became customary to carry a hilya in the form of a scroll, calligraphic study, or an amulet. In the seventeenth century, hilyas developed into an art form with a standardised layout.

Conclusion

Islamic art can be recognised and identified outwardly by its tell-tale signs of how the manifestation of symmetry takes place, or the harmony in size and composition of a structure. For example, what distinguishes the architecture of Muslim Spain from its immediate successors, the Christian Spanish, who enslaved Muslim architects and artisans to re-create the majesty the Muslims had delivered upon Europe. It takes a keen observer seconds to distinguish the sacred inspired and the non-sacred, the harmony of the multiplicity and the one, and the disharmony of imitation. Although many aspects of Islamic architecture remained in use in Spain and then northern Europe (including the rich geometric elements and the famous horse shoe arch), the European imitations of Muslim architecture feel imbalanced and a weaker replica of what the Muslims achieved. The beauty, the imitators failed to understand, was not in the chisel or just the hands of the labourer, but in the Truth that was deeply accepted by the artist, the designer, and then engineer, engraver and painter.

Many European artists entered the lands of Islam between the late 16th and 19th century to understand, analyse, and then copy the art found in Persia and India, but none were able to insert the harmony that came from revelation, none were able to tie together the disparate into the singular.

When Sinan designed mosques, he had a habit to fill the central space of the mosque with light. The light would flood in from the many windows, and the mosque would be incorporated into the complex, making the mosques more than simply monuments to God’s glory but also serving the needs of the community as academies, community centres, hospitals, inns, and charitable institutions. The term ‘Islamic Architecture’ carries with it the beautiful burden of the teachings and values of Islam as declared in the glorious Quran. If the term ‘Islamic’ can only be applied to topics of Sharia, to the practise of religion, of Islamic law and social etiquette, and the Quran certainly does not lay out the blueprints for architectural design, carpets and illuminated manuscripts, then should art and architecture be given the title ‘Islamic’? I will argue yes. The Quran does however have within it the blueprints for Islam, and these designs play out in our world through the creations of spaces that capture and veil the beauty of God, that represent through direct and subtle references to the glory of God, that are inspired by His beauty to show His beauty, that then pull out of the Quran and Hadith, practises of love and charity and turn these into material reality. It is the direct and indirect instructions that have vocalised a design language born out of the sacred truth. It is Islam that inserted curiosity and the seeking of knowledge into the chest of its believers, a religious duty that developed the sciences, caused art, literature and poetry to flourish.

Islamic art derives its beauty from wisdom. Not coincidence.

References

The Silent Theology of Islamic Art by Oludamini Ogunnaike

Architectural Elements in Islamic Ornamentation: New Vision in Contemporary Islamic Art by Jeanan Shafiq

Art of Islam: Language and Meaning, a book by Titus Burckhardt

0 Thoughts on What is Islamic Art?