Introduction

Who was Muhammad Rumi? A Poet, a Faqih (Jurist), an Islamic Scholar, a Theologian and Sufi Mystic and above all a lover of our beloved Muhammad ﷺ.

Born in greater Khorasan, Balkh (now Afghanistan), Mawlana Rumi today is arguably the most popular and most read poet in the world. His name and the English translations of his poems are on the tongue of all new age spiritualists who have tapped into the sacred light that emits from the words of Rumi, and who have then kept Islam out of any understanding they might absorb incidentally. Rumi then is a meme poet, one who deserves no more space than a twitter word limit or the place below an Instagram photo.

The name Rumi comes from the Arabic word for ‘Roman’. Rumi lived most of his life in Anatolia (modern day Turkey), a land that had been only relatively recently been conquered by the Muslims from the hands of the Romans when Rumi was born, his title then was his incidental connection to this land. But for clarity, there is nothing roman about Rumi, his roots and his faith all point to Khorosan, and unlike the near eastern Romans, Rumi was an migrant to what is now known as Turkey.

Why is Rumi so popular?

Poetry is dead, at least in the West. The Poetry genre barely moves any books each year but one man is an exception – Rumi. Mawlana Rumi has been popularised in the west mostly due to the efforts of a single man, Coleman Barks, an American who with the help of other Persian speakers translated the works into English. Barks himself speaks no Persian, has had no regular or reliable access to Persian translations, but has worked to re-interpret Rumi into a language, style that appeals to his world view without being true to the original author – Rumi. The view Barks presents is one absent of God, the Muslim God, of Islam, of the beloved Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, of any orthodox Islam that is part of Sufism. Rumi then is identified as a ‘mystic’, ‘saint’ or enlightened man but never as a Muslim from reading any of Barks works.

“Of course, as I work on these poems, I don’t have the Persian to consult. I literally have nothing to be faithful to, except what the scholars give.” – Coleman Barks

The modern spiritual cauldron that non-Muslims grasp onto has defined the image of Muhammad Rumi. The problem transcends unfortunately into the Muslim readership, notably the non-Persian speakers who rely heavily on popular translations provided to them for digesting the works of a saint and in turn read and understand a body of work entirely different to how the author had intended.

As mentioned, the largest culprit is Coleman Barks. His translations or versions of Rumi have sold over 500,000 copies worldwide. In a world where poetry rarely sells, this is a master achievement.

Let’s examine some examples of the mis-translations or interpretations.

Poor and Accurate Translations

Example One

Consider the famous poem “Like This.”

“Whoever asks you about the Houris, show (your) face (and say) ‘Like this.’”

Houris are virgins promised in Paradise in Islam. Barks avoids even the literal translation of that word; in his version, the line becomes, “If anyone asks you how the perfect satisfaction of all our sexual wanting will look, lift your face and say, Like this.”

The religious context is gone. And yet, elsewhere in the same poem, Barks keeps references to Jesus and Joseph. When he was asked him about this, he said he couldn’t recall if he had made a deliberate choice to remove Islamic references. “I was brought up Presbyterian,” he said. “I used to memorize Bible verses, and I know the New Testament more than I know the Koran.” He added, “The Koran is hard to read.”

Other interpretations that need an honorary mention, for they too are guilty are those by Shahram Shiva, John Moyne, Andrew Harvey and Deepak Chopra. These authors have all made a name for themselves as modern spiritualists, and have had a degree of commercial success in profiting from Muhammad Rumi.

Example Two

“Not Christian or Jew or Muslim, not Hindu, Buddhist, sufi, or zen. Not any religion or cultural system.”

This is not an authentic Rumi poem. This version was based on Nicholson’s translation: “What is to be done, O Moslems? for I do not recognise myself. I am neither Christian nor Jew, nor Gabr, nor Moslem.”

Example Three

“You say you have no sexual longing any more. You’re one with the one you love.”

An accurate translation: “You say, ‘With the body, I am far and with the heart, with the Beloved'”

Example Four

“Love puts away the instruments and takes off the silk robes. Our nakedness together changes me completely”

Accurate translation: “He put harp and (strings of) silk on (his) lap, (and) kept playing this song: ‘I am happy and ecstatic'”

Example Five

“They try to say what you are, spiritual or sexual? They wonder about Solomon and all his wives”

An accurate Translation: “O Love, you are known by the fairies and humans. You are more known than the seal-ring of Solomon”

Example Six

“This night . . . is not a night but a marriage, a couple whispering in bed in unison the same words. Darkness simply lets down a curtain for that”

An accurate translation: “Tonight . . . is not a ‘night,’ Rather, it is a wedding (festival) for those who seek God. It is an elegant companion for those who testify to (God’s) Unity. Tonight is a lovely veil of happiness for those with beautiful faces”.

Example Seven

“If you don’t have a woman that lives with you, why aren’t you looking? If you have one, why aren’t you satisfied?”

An accurate translation: “If you have no beloved, why do you not seek one. And if you have attained the Beloved, why do you not rejoice?”

There are hundreds of examples, perhaps thousands where Rumi’s words have been mis-translated and changed entirely. To either suit a particular ‘spiritual path’ or journey the author wanted, or to purposely steer the reader away from the true message behind the words of a very Muslim scholar and saint. Coleman Barks, who continues to take focus in this study, even includes entirely new words and phrases that Rumi never uses. In one example Rumi is quoted to have used the word Hindu, Buddhist and Zen in one of his poems but these are all false. There is no evidence at all that Rumi was familiar with these religions other than what was mentioned in the Quran. But for the purpose of mass appeal Barks has applied a false translation to say ‘look Rumi wasn’t a Muslim, if you’re a Hindu or Buddhist, he is equally relevant to your spiritual path’.

The criminality behind modern interpretations

The most troubling aspect of the translations is how some words, phrases and then the intended message behind the words are changed so much that Rumi himself is misunderstood entirely from being a very pious Muslim to a highly charged ‘modern sexually liberated’ man.

When Barks was asked why his interpretations of Rumi are so popular, Barks is quoted as claiming his work is closer to the true ‘essence’ of Rumi. One has to perform incredible mental gymnastics to understand how a white man that speaks absolutely no Persian, nor understands even basic principles of Islam can make such a big claim.

Barks translations are guilty of many things, while some claim that certain Persian words have double meanings or there is ambiguity, there are far greater cases where the essence of a poem has been slanted towards a very sexual direction. In these cases it is hard to believe this an innocent mistake, but rather a purposeful direction taken by the interpreter Barks.

Rumi was a mystic; he remained a pious devout Muslim inclined towards ascetism. Adultery, participating in orgies, and full nudity – all indicated in these translations are forbidden in Islam and appear nowhere in original Rumi works.

Rumi in meme culture

With the mass adoption of social media and the rise of the meme culture surrounding us, we must absolutely disassociate ourselves from placing the sacred text of our scholars and saints on these platforms. While the temptation is high, lets accept that Rumi is not a new age pop psychologist who can address our specific or general issues of love, self-identity and low self-esteem. For Rumi the Qur’an was his blueprint, the Prophet ﷺ was his beloved, and God was his final union.

The spiritual gap or hunger that is present in the west is where the appetite for these interpretations arise. As the western obsession with selective eastern religions and traditions grows, we must be prepared for our literature, music, and wider culture to be adopted in selective terms, where what the west considers ‘acceptable’ or interesting is picked with the ‘Islamic’ or ‘Muslim’ part discarded. We must be aware of our own education and how we digest what is presented to us.

Example Eight

“Listen and obey the hushed language. Go naked”

An accurate translation: “So runs his whispered tale, ‘Go not without the veil’”

When Coleman Barks was asked to explain his method of translation, he said: ‘Yeah, the fundamentalists or people who think there is one particular revelation scold me for this.'”

Example Nine

“All my mysteries are images of you — Night, be long! He and I are lost in Love.”

The translation is over-sexualised. The intended meaning of the lines suggests for one to stay awake and long for the beloved, for more worshipping is required. Again, there is no way for one to know this line is about God.

Example Ten

In other places the spiritual elevation placed in the words of Rumi has been reduced to pop-psychology.

“All my life I tried to please others, Pleasing myself he is wishing me.”

The original meaning has to do with the tendency of the spiritual seeker to become attached to “spiritual stations” (maqamat), or levels of spiritual attainment- which can be a barrier to seeking God directly.

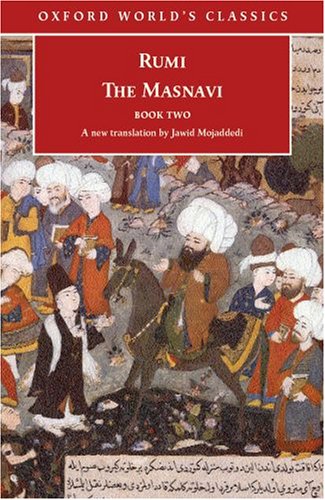

The Masnavi, the masterpiece produced by Rumi over 13 years has been termed as the ‘Persian Quran’. Rumi himself described the “Masnavi” as “the roots of the roots of the roots of religion”—meaning Islam—“and the explainer of the Koran.” And yet little traces of religion remain his translations.

Translators and theologians of our time have had to reconcile with widely accepted Islamophobia of our time with the mass appeal of certain Islamic cultures. Including poetry (Hafez, Saadi, Omar Khayyum) and Islamic Art and Architecture (almost all major museums in the west include exhibitions on Islam), so what is the result? How do you balance an appreciation for one aspect of a medieval religion and then at the same time promote the flowers that blossomed in its bosom?

You do it like this:

- Mistranslate and interpret the literary works to such a degree that even Muslims use your sources for referencing their culture. If Islam is taken out, who can claim and who can reinstate? With Rumi now so popular globally, it is too late for new translations to become the standard when Rumi is already a meme poet.

- You exhibit the richness of a culture as a by-product of a civilisation, not of its faith. Persian Art, Indian art, Moor and Mamluk architecture – there is no Islam necessary.

- When all fails and it is not possible to de-tangle Islam from the poets or scholars, you recognise the connection but ensure its either seen as a one-off period in an other-wise dark period of backwardness and intolerance. Finally, you ensure that no Muslim today can claim heritage to the rich civilisations of their ancestors. The exhibitions in the British Museum or Louvre that present for all to see the marvel of Islam art are narrated as one that belonged to a period that is long over. The native today is a dumb, stupid and weak by-product of a wealthy ancestry.

Religion for many western translators of Rumi, or Hafez or Avicenna, or Ibn Rush is purely an obstacle. The view is that these people are mystical, geniuses and achieved not because of Islam but in spite of it.

Was Rumi really a pious Muslim?

Rumi writes:

“The Light of Muhammad has become a thousand branches (of knowledge), a thousand, so that both this world and the next have been seized from end to end. If Muhammad rips the veil open from a single such branch, thousands of monks and priests will tear the string of false belief from around their waists.”

and

“I am the servant of the Qur’an as long as I have life.

I am the dust on the path of Muhammad, the Chosen one.

If anyone quotes anything except this from my sayings,

I am quit of him and outraged by these words. “

Why has this happened?

[ the following are extracts from an article by the New Yorker linked at the end]

“Discussing these New Age “translations,” Omid Safi said, “I see a type of ‘spiritual colonialism’ at work here: bypassing, erasing, and occupying a spiritual landscape that has been lived and breathed and internalized by Muslims from Bosnia and Istanbul to Konya and Iran to Central and South Asia.” Extracting the spiritual from the religious context has deep reverberations. Islam is regularly diagnosed as a “cancer,” including by General Michael Flynn, President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for national-security adviser, and, even today, policymakers suggest that non-Western and nonwhite groups have not contributed to civilization.”

“For his part, Barks sees religion as secondary to the essence of Rumi. “Religion is such a point of contention for the world,” he told me. “I got my truth and you got your truth—this is just absurd. We’re all in this together and I’m trying to open my heart, and Rumi’s poetry helps with that.” One might detect in this philosophy something of Rumi’s own approach to poetry: Rumi often amended texts from the Koran so that they would fit the lyrical rhyme and meter of the Persian verse. But while Rumi’s Persian readers would recognize the tactic, most American readers are unaware of the Islamic blueprint. Safi has compared reading Rumi without the Koran to reading Milton without the Bible: even if Rumi was heterodox, it’s important to recognize that he was heterodox in a Muslim context—and that Islamic culture, centuries ago, had room for such heterodoxy. Rumi’s works are not just layered with religion; they represent the historical dynamism within Islamic scholarship.”

“Rumi used the Koran, Hadiths, and religion in an explorative way, often challenging conventional readings. One of Barks’s popular renditions goes like this: “Out beyond ideas of rightdoing and wrongdoing, there is a field. / I will meet you there.” The original version makes no mention of “rightdoing” or “wrongdoing.” The words Rumi wrote were iman (“religion”) and kufr (“infidelity”). Imagine, then, a Muslim scholar saying that the basis of faith lies not in religious code but in an elevated space of compassion and love. What we, and perhaps many Muslim clerics, might consider radical today is an interpretation that Rumi put forward more than seven hundred years ago.”

Where do we go from here?

There is a clear shortage of criticisms of popular Rumi translations (or as we have been saying, interpretations), so this must continue. We must place literature boycotts on these loose interpretations, on these or any texts that claim to represent the sacredness of entirely Muslim authors. The colonisation of our literature might grow in the west, but as Muslims or people of the east, we must recognise the dangers that we face when we make non-Muslims our teachers, especially those that actively work to remove Islam from inextricable.

What translations to avoid?

- Anything by Coleman Barks

- Other interpretations that need an honorary mention, for they too are guilty are those by Shahram Shiva, John Moyne, Andrew Harvey and Deepak Chopra. These authors have all made a name for themselves as modern spiritualists, and have had a degree of commercial success in profiting from Muhammad Rumi.

Recommended Accurate Translations

Jawid Mojaddedi, who has aspired to translate all six books of the Masnavi into English. Four of them are completed and available on Amazon.

References and further reading:

http://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-erasure-of-islam-from-the-poetry-of-rumi