A few months ago, I wrote an article titled The Erasure of Islam from the works of Rumi from English translations. This was in response to countless queries I was receiving to recommend a reliable translation, ideally one that was not by Coleman Barks. The response to this will always be the translations by Jawid Mojaddedi until someone better comes along.

This article sparked some debate into what harm there is in translations, and whether poetry could ever be accurately translated. The conclusion presented was that certain translations of Rumi’s work were not translations at all, but imaginative interpretations.

Rumi is the most popular poet in the world. Fact. Before Rumi, the Persian poet Omar Khayyam was the most popular poet in the West for over a hundred years.

In the 1980s however, Playboy magazine published several couplets by Rumi in its publication and it was a sign of changing time. It was the first time the pornography industry had become interested in poetry. Could it be because Rumi had become associated with sensual love? With wine and intoxication? Often the translator responsible for Persian poetry (or we should just call them interpreters) spoke little to no Persian, removed Islam partially or completely from couplets, then inserted themes, rhymes, icons and messages that would transmit the writers own view of spirituality and mysticism.

Rumi it seemed, alongside a few other Islamic (and non-Islamic) poets, thinkers, saints, had become the vessel for Western infatuation with eastern esotericism (spirituality and mysticism). The West, it can be argued has become void of spirituality and meaning, with rationalism and materialism as its primary religion (Christianity it appears was thrown out with the ‘enlightenment’). I argue the average person in the west feels the emptiness in this materialistic Godless society and looks elsewhere for spiritual fulfilment. This new-age need for a godless feelgood religion that has no church or temple has fed this thirst for secularised Rumi. Whether it’s Madonna pushing Kabbalah, Tom Cruise and Scientology, or your Hare Krishna hippies counterculture that followed the Beatles back from India into the streets of western capitals, there is a hole in the West that yoga and meme spiritual poetry will not fill.

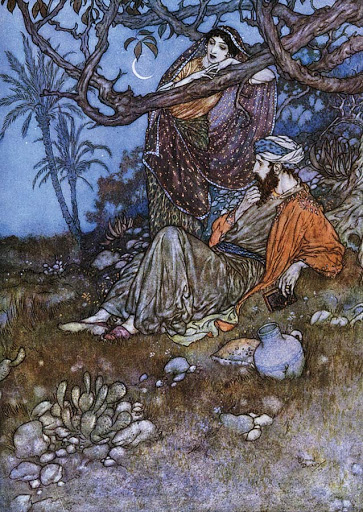

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

In 1859, an English man named Edward FitzGerald ‘translated’ the poetry of the 12th century Persian Astronomer and Poet, Omar Khayyam. FitzGerald’s translation was rhyming and metrical, and rather free in its interpretation. Many of the verses written by FitzGerald are paraphrased, and some of them cannot even be traced to Omar Khayyam. To a large extent, the Rubaiyat can be considered original poetry by FitzGerald loosely based on Omar’s quatrains rather than a “translation” in the narrow sense.

By the 1880’s, “Omar Khayyam Clubs” (fan clubs) opened up in the English-speaking world, with FitzGerald’s extremely loose translations of Omar Khayyam becoming best sellers.

FitzGerald however was not done with simply re-writing Omar Khayyam, he directly attempted to remove Islam from his poetry. FitzGerald belonged to what is called the ‘Pre-Raphaelites’ (a set of English poets, artists and creatives who wanted to revive the honesty and spirituality in Christian art). FitzGerald began by claiming that Omar was “hated and dreaded by Sufis, who he called hypocrites”. Going as far as to claim, with support from his fellow Pre-Raphaelites that Omar was despised by other great Sufis such as Shams Tabrizi, Attar and Al-Ghazali. Who claimed Omar was not a ‘Sufi’ but a ‘free-thinking scientist’. A brave set of propositions by English writers and artists who spoke no Persian, had access to no original manuscripts but were keen to make Omar Khayyam one of theirs. The comedic value in mediocre English artists attempting to make such claims deserves applaud. In recent years news research even claims that Khayyam wrote no poetry himself, but the work of authors over a span of 200 years wrote quatrains that were attributed to the famous scientist (why, its not clear but perhaps because it would stick more if a name as big as Khayyam could be used, similar examples exist of poetry assigned to other Persian scientists including Ibn Sina).

Coleman Barks was asked once why he removed Islam from the poetry of Rumi, to which he replied:

“I was brought up Presbyterian,” he said. “I used to memorize Bible verses, and I know the New Testament more than I know the Koran.” He added, “The Koran is hard to read.”

Rumi has become the ‘Prophet’ of many people who associate themselves with no God or faith, he represents the age of a ‘feel-good’ religion, where spirituality is internal, goodness inherent, and kindness inevitable. All one needs to be at peace are beautiful harmonic verses that speak the ‘human language’. No Allah. No Prophet. No Quran. No Jibreel. Nope. No religion in Rumi. Please.

We now need to ask and answer the question: What do ‘we’ owe the West, if anything, for making Rumi this incredibly popular. Is there gratitude owed to the West for the translations of, importing to, and learning from the works of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi.

Entry of Rumi into the West

It was in 1898, that James Redhouse wrote in his introduction to his translation of the Masnavi, that “the Masnavi addresses those who leave the world, try to know and be with God, efface their selves and devote themselves to spiritual contemplation”. For those in the West, Rumi and Islam were now separated a long time ago.

Some academics trace this removal of Islam from Islamic poetry back to the Victoria period (1837-1900). Translators and theologians could not reconcile the notion that a desert religion that the Christian Europe had been at war with for centuries, with its bizarre moral and legal code could produce beauty found in Rumi, Hafez or Khayyam. Later, Rumi became vastly more popular through translations by Nicholson A.J. Arberry (fluent in Persian), and Annemerie Schimmel. Rumi was to become a big name in the English-speaking world. Then came Barks. It was his interpretations of Rumi that skyrocketed Rumi into the hands of the young college student, pseudo poet/intellect, and the curious Westerner who wanted a taste (a mild one) of the mysticism of the East.

Barks however does not read or write any Persian.

“Of course, as I work on these poems, I don’t have the Persian to consult. I literally have nothing to be faithful to, except what the scholars give.” – Barks

Barks however did dabble in Sufism after which he had a dream in which a stranger appearing in a light told him “I love you”. Barks then began to rephrase other English translations into his own poetry. Thus, begins the re-framing, re-writing, and re-creation of Rumi in the imaginations of one man. Barks interpretation of Rumi’s poetry have become the most popular in the world. There is a high chance if you have read Rumi in English, you have read his work. He is to Rumi, what FitzGerald was to Omar Khayyam.

What do we then owe Barks for his contribution to the spread of the very Muslim Rumi?

For one, Barks began by removing most, if not all references to Islam from the work of Rumi. Sufism that Barks entertained did not insert, but rather encouraged him to de-couple all Islamic references from the Masnavi. What we in the Muslim world call ‘The Persian Quran’, Barks began to rephrase into pop-Sufism for dummies. The Masnavi in its essence teaches its readers on how to reach their goal of being truly in love with Allah. Instead, Barks has delivered the world a corrupt interpretation that has replaced the love of God with the love of a human lover, the anticipation and meeting with God, with sexual encounters, the pain of separation and ecstasy that comes with loving God with jealousy, grief and intoxication found in drunkenness. For Barks, who understands nothing of Persian or the richness of Islamic poetry, forget nuance, even the basic elements of metaphors escape.

Let’s revisit some interpretations by Barks.

Original:

“Whoever asks you about the Houris, show (your) face (and say) ‘Like this.’”

Barks Interpretation:

“If anyone asks you how the perfect satisfaction of all our sexual wanting will look, lift your face and say, Like this.”

Original:

“You say, ‘With the body, I am far and with the heart, with the Beloved’”

Barks Interpretation:

“You say you have no sexual longing anymore. You’re one with the one you love.”

Original:

An accurate translation: “If you have no beloved, why do you not seek one. And if you have attained the Beloved, why do you not rejoice?”

Barks Interpretation:

“If you don’t have a woman that lives with you, why aren’t you looking? If you have one, why aren’t you satisfied?”

Ok sure there are issues with translations, true, but Barks essentially gave the non-Persian world Rumi. Without him, none of us would be reading Rumi. Right? Including Muslims!

Rumi, although highly popular in the English language, is vastly more popular and present in the rest of the non-English speaking world. A reader of only English may view Rumi and other ‘Sufi’ poets as essentially ‘dead’, and argue that the average Muslim does not understand or appreciate the mastery of Rumi or other poets. This view is limited, as the analysis and conclusion would be drawn from an English world view. The richness and depth of Islam felt is vastly different if one sits by a pulpit in Old Cairo, Delhi, Isfahan to London, Montreal or San Francisco. If one wants to hear the words of Mawlana Mohammed Jalaluddin Rumi or Hafez, or Mohammad Iqbal, in a Mosque, Madrassa or Café, they will have to visit the East where these poets are often memorised by heart by the old and young and recited in debate, poetry recitals and even in political discourses.

Anecdote, my first introduction to Rumi and his message came whilst sipping tea in a rundown café in Shiraz. The reciter, a young man, trembled with excitement and love as they pulled a mini copy of the Masnavi out of their bag to read a few verses that they felt suited the conversations we were having. After the recitation was over, I replied “do you know what they say about Rumi in the West? they say he wrote these lines for his lovers in a state of intoxication”. In disbelief and shock, the young man refused to accept what I had just said. He responded “Mawlana is talking about Allah, this book in my hand is a guide to the Quran”.

I nodded and we left it there.

Whilst there are many reasons to mourn the loss and lack of appreciation of saints, scholars, poets and philosophers in the Muslim world (the Golden-age is long over), it is foolish to think the experience of Islam in the West is parallel to Islam in the East.

Rumi is alive.

Rumi has inspired poets and scholars for over 800 years

Rumi claimed he was inspired by Al-Ghazali, Attar, Baha-ud-din Zakariya, Bayazid Bistami, and of course Shams Tabrizi. The list of people he inspired is even longer. Including, Jami, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob, Abdolkarim Soroush, Hossein Elahi Ghomshei, Muhammad Iqbal, Hossein Nasr, Yunus Emre….and Coleman Barks.

So, what does Rumi or other poets owe the West?

While some of Barks verses and interpretations are admirable for their poetic beauty, he is a poet and deserves some accolade. We must also remember the light of the Truth, of the sacredness that leaks (even if in fractions) into interpretations, translations, no matter how corrupt they are.

Knowledge and its pursuit are a noble cause. No book is more important than the glorious Quran, and then the teachings of the beloved Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) for us understanding our faith. The Masnavi was written as a revealer of the Quran. The Masnavi attempts to explain the universals and the particulars. It was Rumi’s attempt to bring us closer to God, the One God, Allah swt.

Rumi in the West Today

Any ‘translations’ of Rumi by non-Persian speakers often rely on others translations. Unfortunately, not knowing the original language, the ‘translators’ “poetic inspiration” often leads them further away from the original meaning and spirit of the work- instead of closer, as one might hope. If the most popular translations (or interpretations) read today are by authors who have changed the message of the Masnavi (intentionally or unintentionally), what message is the Masnavi sending and how is it being received?

Do we as Muslims, need to wait for the European to discover our rich history, only to re-tell it to us in his own way in English or any other European language? How many young Muslims, unaware, have let interpreters like Barks introduce Rumi to them? Or shall we stop trying to keep the sacredness of Rumi alive in any and all translations?

To a non-Persian speaker, it is difficult, if not an impossible task, to separate a verse closer to the original to one that is entirely different. How can we tell from Barks translations which verse is accurate and which is not? How does the reader know? Does the Masnavi still act as the revealer of the glorious Quran? Or are we now entering a realm of spirituality and mysticism where the Islam of Rumi is less important, but the ‘feel good’ sensations from verses are the goal? Does integrity matter in translations and interpretations? Or are rhymes and pop-Sufi couplets that act as transient forces between the Islamic east and rationalistic West more critical?

If some western readers find Islam through interpretations (no matter how accurate), should we accept a western reading of Rumi that has no clear religion? No Allah, no Messenger, No Jibreel, no Quran? The glorious Quran was first translated into English in the 17th century. The intended purpose was twofold – one, to provide a scholarly text for Christian scholars to study and refute, and secondly, to feed mistranslations into the European world to reveal the “true darkness” of this desert religion. Should we celebrate and applaud the early European translators of the Quran? Should Islam, in its true beauty, remain in the works of Rumi and other Islamic poets? If the West needs to learn and ‘build bridges’ between the ‘Secular’ West and Islamic East, should not Islam in all its oddities remain in work of Rumi?

Unlike before, we now have excellent translations of Rumi. Barks has had his time; we must now reject every and all translations and interpretations that remove the sacred Truth of Islam out of the works of Rumi and other very Islamic poets. Jawid Mojaddedi, a native Persian speaker has released the best to date English translations of the Masnavi.

I am the servant of the Qur’an as long as I have life.

I am the dust on the path of Muhammad, the Chosen one.

If anyone quotes anything except this from my sayings,

I am quit of him and outraged by these words.

– Mawlana Rumi