Shiraz, the sweetest of songs is the start, centre and end of every poetic pronunciation to come out of Iran. A song to disturb the conscious but calm the heart, a song to drive a saint mad, a song to lure and seduce every conqueror. Hafez, the master of Shiraz is the louded bulbul of all. It is said that he had memorised by heart, all the works of Jalal-din Rumi, Farid ud-Din Attar and Nizami and that by hearing his father’s recitations of the Quran, he memorised the greatest book of all. Hafez, who never left Shiraz, almost had his throat cut by Timur, who conquered Shiraz but was disturbed by a verse Hafez had written:

“If that Shirazi Turk would take my heart in hand

I would gift Samarkand and Bukhara for her black mole.”

By her, Hafez means Shakh-e Nabat, a woman Hafez was taken in by, and the Shirazi Turk he means Timur. Samarkand and Bukhara were the capitals and finest cities of the Timurid empire, and at these words Timur angrily summoned Hafez.

“With the blows of my lustrous sword”, Timur complained, “I have subjugated most of the habitable globe… to embellish Samarkand and Bokhara, the seats of my government; and you would sell them for the black mole of some girl in Shiraz!” Hafez replied, “Alas, O Prince, it is this extravagance which is the cause of the misery in which you find me”. So surprised and pleased was Timur with this response that he dismissed Hafez with handsome gifts.

The recommended journey into Shiraz must be from Yazd. For a garden is appreciated when one has tasted but only the fire of the desert. Yazd, an unforgiving station and resting place of the sun, where man submits to His will, where the faithful, of Zarathushtra once reigned, today stand in the shade and watch as the true believers of the Truth grapple with the forces of nature.

Shiraz then is a full day’s journey south. One passes mountains and wide valleys, yellow rocky deserts and dried lakes but then as the first maiden sun begins to sink into itself in pushes out a red hue, the light that remains reveals the dark green pastures of the province of Pars, in which Shiraz is the beautiful adornment. Here one finds shepherds, wanderers and the lost children of a time that is no longer. Caravans can stop to replenish and take stock, one may rest and drink sweet tea and if one is already under the spell of the further yet valleys of Shiraz, he may shut his eyes and make this his place to rest. But what a foolish act it is to be this far, this close, and not enter the walls and gardens of Shiraz.

Shiraz knows no parallel in all of Persia and the world. Sought by all but plucked by none, it remains a mole on the cheek of the most beautiful of Muslim lands. Shiraz has been saved it seems, most certainly by plan, to deliver to the thirsty, hungry and blind of this world – the endless stream of verses that flow in abundance from the lips of its poets and saints.

In the year 1216 as the forces of Genghis Khan laid siege and delivered death to all of Khorasan, the rulers of Shiraz offered tributes and submitted voluntary to spare themselves the same fate as that of Neyshabur. Again in 1382 as Tamarlane entered Shiraz, the local Shah accepted surrender. In the 13th century, Shiraz became a leading centre of arts and letters. Many classical geographers would name Shiraz as Dar el-Elm, the House of Knowledge. Amongst many that were born and cradled by this city of culture were the poets Sa’adi, and Hafiz, the mystic Roozbehan and the philosopher Mulla Sadra.

Each time I visit Shiraz, I find dwelling in the centre of religious quarter of Sang-e-Sia (‘Black Stone’), an area dotted with more saints than this traveller can accurately recall but I will do my best to share the most prominent with the will of Allah. I was not able to find out about the significance of the name.

Shiraz for most of its Islamic history had been a city under Sunni Islam, but today, like most of Iran, it is under the schools and teaching of the Shiites, and the sites of pilgrimage today reflects this. But it is also a holy city for the Baha’i faith that few know, though the centre of this pilgrimage sight was destroyed at the commencement of the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Bibi Dokhtaran Khadija

The shrine of Bibi Dokhtaran can be seen from afar. Its large dome dominates the old city. Simple in its appearance it has either lost or never had any tiles, which would be strange given the Persian practise and love for mosaic tilework on all shrines. As with the outside, the inside is plain and shows a modest picture. In the evening sky, the dome is lit green with strong flood lights. A lighthouse for the lost pilgrim, it either led you back to Sang-e-sia, or it took you close enough to the major shrine of Shah Chirag, which is in very close proximity.

Square in space, the shrine is surrounded by a dry garden and is today one of the few important shrines in Iran dedicated to a woman (the other is in Qom). The story of Bibi Dokhataran is one of escape from the Abbasids who were responsible for the prosecution of many of Imams and their descendants (for they feared a political and religious revival that could dethrone and de-legitimise their rule). Bibi Dokhtaran was the daughter of Imam Zayn al-Abidin (or known as Ali Ibn Husayn) the fourth Imam of the Shiites, who fled the city of Baghdad to Persia to seek safety, as we will learn would be the case for many descendants of the other Imams. Persia, on the edge of the Abbasid empire, provided shelter for many who were prosecuted.

During the evenings, voices of women can be heard inside all over the quarter of Sang-e-sia. Songs of praise, of remembrance, and at other times, emotional recitation of the holy Quran during any religious holiday can be heard by a passer-by. It is an unusual but beautiful experience to hear such singing and recitation, as it is not common to hear women recite loudly in any ceremony or event in Sunni lands. I would slow down my steps each time I suspected there was a gathering and would wait for the beautiful Persian Arabic dialect to enter my ear.

I entered the shrine during one early morning when the caretakers, who are all women and who dress only in black (as is mandated by the state and cultural norm), swept the surrounding garden. I expected some objection to my presence, as I had wrongly assumed, that I, a man, would not be welcomed inside especially if there were other women worshippers inside. As I entered it became clear I was alone, and I studied the shrine and its interior carefully. The shrine sits in the centre, immediately under the grand dome and the flooring is carpeted but the rest of the shrines walls and roof are in poor condition. There is no attempt to make them look beautiful, and unlike other shrines in Iran, there is no glass mirror work anywhere inside. I welcomed this departure from common design and focused only on the shrine.

Hafez of Shiraz

“I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold.

There is no protection for my head other than this door.“

Shiraz is a grove of paradise that surpasses all others, it is a city that appears to have been created as a beautiful excuse so Hafez could lay claim to its streets, walls and doors. Hafez claims to have been influenced by Ibn Arabi, Nizami and Attar, he is the child Ghazal (a lyrical poem himself) then of an order of religious mysticism that continues to intoxicate the faithful, and confuse and derail the confounded even more so.

Walk through the streets and bazaars of Shiraz and you will find Shiraz is nothing more than a provincial town, but enter its gardens unguarded and it will pull your ear and feed you its sweetness. No other city surpasses the beauty and melody of Shiraz, not even Isfahan.

Eyes closed, but heart beating, Hafez today can be found in North of Shiraz, not too far from Saadi. Visit him before maghrib (sunset) if you want to speak to him in solace, but return in the late evening if you want to sit and laugh with him. Hafez it appears has stirred the imaginations of many, and this author has also been infected. Today the verses, the Ghazals, of our beloved Hafez are at the centre of what I think should be called popular fanaticism amongst the common people of Iran. A proud people, the Iranians are without a doubt the singular most creative people, offer them a brief moment and hours will lapse and you will beg ‘more, more’ but the poetry turned melody will not end.

However, and this is important, Hafez of today is not the Hafez who stood across from Timur, the Hafez of today is the meme equivalent for a people who in their hunger for culture and nationalistic fervour have transformed a giant into a lowly figure. Hafez has been re-imagined for a modern Iran where despite fervour theocracy being the order of the day, Persian identity comes first. Hafez has had any Islamic influence extracted out of him, forcibly so, a faith that was integral is replaced with empty and foolish romanticism that delivers a truly painful translation.

This phenomenon is not singular to Hafez, his forebearers and contemporaries have been reinterpreted to fit the same narrative. Saadi, Ferdowsi, Attar and Jalal-ud Din Rumi are seen today as great Persian poets in spite of their Islamic heritage, not because of. Where God once took centre stage in their poetry, today the beloved is a woman and in some disturbing translations, young boys. Some blame is on the modern Persian poetry movement, but where the poetry is translated to languages outside of Persian, we can unequivocally state the culprits are the non-Muslim authors who have re-written and re-imagined the essentials of the original poetry.

If you visit Hafez, then bear in mind the position of this man amongst the majority of his readers, especially the younger generation. It will be easy to be convinced that Hafez was a regular visitor of taverns, who spun stanzas to describe his love and seduction of this worldly love and its pains, that his noose was a woman’s tassel but not his love for the beloved of all beloveds.

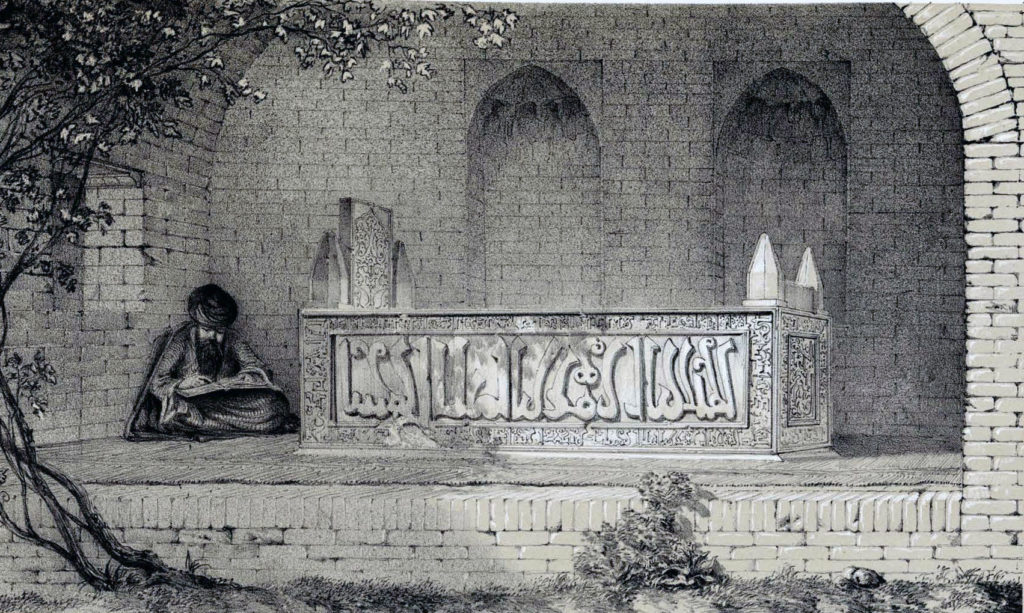

Hafez today is buried in perhaps the busiest garden of all. For centuries the resting place of this saint was mostly forgotten, his name but another name amongst the great poets. It was then during the late 19th century that a local Shirazi ruler paid patronage and invested in elevating the state of this great poet. His tomb that had been outdoors and exposed, had a wooden structure built and the gardens cleaned. Then in 1901, a decorate Iron transenna was added around the tomb but it was not until 1931 that the garden underwent major repairs, the orange groves trimmed, and a French architect tasked with redesigning the monument that see today. The iconic dome, in the shape of a dervish hat are held up by eight columns, each ten metres high with inscriptions from Hafez poetry found on the inside of the dome.

This is Hafez today. Surrounded by aimless fanaticism, where the sounds of birds and his poetry being recited is fed through loudspeakers that themselves barely hide the murmur and laughter of visitors who only want to be around greatness, but who have spared no moment, to reflect, and to understanding the depth of even a singular verse.

But there are exceptions. I witnessed a flock of women, adorned in all black Chadors, surrounding the marble stone that rests on top of Hafez. These women, with Qurans in their hands loudly recited verses from this great book and then read lines from Hafez himself. The entire garden was on high alert as Islam had re-entered, the tourists with their cameras and haughty attire were pushed back, and the mesmerising effect of Hafez was pushed back to Hafez, for what must it feel like to read true Hafez to Hafez.

It should not surprise one then that Iran continues to produce great literary men and women even today. Poets who better reflect the changed society of Iran from its Sunni Sufi/Mysticism days, where there is no need to re-interpret what is already relevant and acceptable. For example, Forough Farrokhzad, Sohrab Sepehri and Shamlou continue to sink the the Persian speaking world into an oblivion of complete submission. Every young Iranian I would meet in Iran would reference Hafez and Shamlou, whether to remark on a note on love or on politics. Find me another people, another world like this.

Saadi Shirazi

بنیآدم اعضای یکدیگرند

که در آفرينش ز یک گوهرند

چو عضوى بهدرد آورَد روزگار

دگر عضوها را نمانَد قرارتو کز محنت دیگران بیغمی

نشاید که نامت نهند آدمی

“The children of Adam are the members of one another,

since in their creation they are of one essence.

When the conditions of the time brings a member to pain,

the other members will suffer from discomfort.

You, who are indifferent to the misery of others,

it is not fitting that they should call you a human being.”

Abu-Muhammad Muslih al-Din bin Abdallah Shirazi (or Saadi) lived a life of extraordinary experiences at the most extraordinary of times. Born in Shiraz at the precise moment the Mongols had ravaged Iran, he spent thirty years of his life as a wanderer, some records say to escape the war and hostility from the Mongol invasion, but it appears to me he had questions he needed answered and these could only be put forth once he left his home. Saadi, enrolled at the Al-Nizamiyya in Baghdad (the largest university in the medieval world), where a hundred years earlier Al-Ghazali was a teacher. The glow and magnetism of Nizamiyya pulled the genius of the Muslim world, and they all answered the call. Saadi, whilst in Baghdad would also experience the destruction of his university by the Mongol Ilkhanate during the sack of Baghdad in 1258. An event of such seismic stature it would blow out the golden age of Islam, one that would never be re-lit the same way again.

One enters the garden of Saadi through a narrow gate, guarded by a stubborn and unusually rude man, who scrutinises the visitor and his ticket very closely. Once inside, a stoned pathway with Cyprus and Orange groves surrounds and the sweet scent of Shiraz envelops. Somewhere inside this garden a speaker is located which plays a beautiful recitation of the poems by Saadi, mostly from his famous Gulistan.

A shallow stream takes one straight up through to Saadi, who is enclosed inside a tall structure with an ordinary dome, but once inside the height and space impresses once the way the tomb of Hafez does not. This is a tomb built to keep out the world and it does. Saadi enjoys the peace that our poor Hafez cannot.

Saadi left Baghdad and travelled to the levant, where at Acre he was captured by the crusaders and imprisoned for seven years. Digging trenches at the fortress of Acre, he performed hard labour until he was released after the Mamluks paid ransom for Muslim prisoners. It is either an incredible coincidence, or none at all, that the Mamluks would go on to defeat and end the conquest of Mongols, the same force that pushed our saint this far into the levant. Saadi would travel to Jerusalem, and then join the pilgrimage caravan and head to Makkah and Medina.

The Mongols however would not leave the area for another few decades. A wanderer, Saadi travelled all over the region, living in refugee camps in poverty, he would meet bandits, men of high scholarly education, the poor who once accumulated high wealth, men with power who now were themselves mere slaves. For another twenty years this would be the life for our saint, who himself torn and in a state of turbulence, felt the most troublesome times in the history of Islam. Returning to Persia, his poetry changed and he began to write for the ordinary, with the flower and its scent plucked and blown away, Saadi discarded the tradition of flowery language and purposeless Persian romanticism and wrote to educate and offer hope to the wider populace, the broken Persian, not the lofty elite who sought eloquence and praise from the poet. Saadi died in 1292 in Shiraz, his achievements even today are barely known and his poetry fills the textbooks of school children in Iran, an audience that Saadi had in mind when he wrote. If the reader is curious to read of Saadi, his Gulistan is the book to pick up. It is reckoned that in the Gulistan there are some forty direct quotations either from the Qur’an or from the Hadith.

Recommended Reading:

Shah-e-Cheragh (‘King of Light’)

If you visit Shiraz for pilgrimage today, you are visiting the funerary monument and mosque of Shah Cheragh. It is said that the brothers Ahmad and Mohammad are buried here, who are the children of Musa al-Kadhim (the 7th Shia Imam), a man also revered by Sunnis as a renowned scholar. The two brothers, as Bibi Dokhtaran, took refuge during the Abbasid period to escape persecution for their Shiite faith.

The mosque and the two shrines for the brothers are secured on all sides by strict security. No man or woman can enter without being searched, large bags are not allowed and if you are a woman, you must adorn the traditional Iranian ‘Chador’. The religious institution that supports and funds this pilgrimage site is organised and well-funded with several expansions in the last few decades and ongoing restoration work. The site is so large it has absorbed the old Jameh Mosque of Atigh, which is now a forgotten corner of this lavish site. If one wants to enter the old Jameh Mosque, which I highly recommend, enter before the hours of sunset, for after large wooden doors that control and the entrance are locked.

The site of Shah Cheragh remains important for Shirazi’s and visitors alike. Despite my refusal or perhaps failure to be drawn to shrines, such as these, I am constantly pulled towards this space. It might be that my own faith, which is entirely inward-looking, seeks some moments, an outward celebration and in Iran, only the shrines of Imam Zadehs (relations of the Shiite Imams) satisfy that urge. I have joined the mandatory Friday congregational prayer many times at Shah Cheragh, and each time it feels as if it is the day of Eid given the numerous pilgrims and celebratory mood in the air. This shrine is a fine example of Iranian Qajar architecture, with many new additions, and perhaps above all, it has the most impressive mirror work I have seen in any shrine in all of Iran.

If you visit the shrine during the early hours of the morning, after the Isha prayer, you will find no crowds. It is then that you can sit by the sweet-scented graves of the two blessed brothers and read Surah Fatiah. Each shrine has multiple custodians (usually older men with wonderful white beards) who guard and guide pilgrims. Iranians have made it a custom to enter the shrine from one door and to leave from another, ensuring that one’s back is never shown to the shrine, a practise that is common across the South East Asian subcontinent too.

If you do visit the shrines during the height of day, when the sun is strong, you will find hidden in the caverns of the shrines the poor and hungry, the travellers and the ordinary, asleep in the coolness of the shrine.

Ali Ibn Hamze

Cross the nineteenth century bridge over the Khosk River (‘Dry River’) and you will spot the shrine of Ali Ibn Hamze. A relative of the fourth Shia Iman, this shrine is a much smaller version of Shah Cheragh.

The bulbous dome is entirely Shirazi, the mirror inside is said to be imported from Italy, and the shrine also has a mosque attached where the daily prayers are performed. Inside the courtyard one can seek shade under the tall trees that deliver great peace during the height of day and night. The shrine is well placed that any traveler would pass it if he wishes to enter the heart of Shiraz or visit the south of the city. Without a plan, I visited this blessed shrine five times and I would enter its grounds without intention. The most immediately noticeable sight is the placement of hundreds of tomb stones on the ground such that one is unable to avoid stepping on them.

Cross the river south again and walk eastward and you will find the only Sunni congregational mosque in Shiraz. Built in the last few decades, its worshippers are mostly Afghan refugees and those from the province of Sistan and Baluchistan.

Ruzbihan Baqli

“His speech is like a rose that flutters apart once grasped in the hand, or like an alchemical substance that turns into vapor when barely heated. His language is the language of perceptions; he praises the beautiful and beauty, and loves them both.”

Abu Muhammad Sheikh Ruzbihan Baqli the poet, mystic and Sufi rests today at the centre of old Shiraz. Nested between ordinary commercial businesses and across the path from the beautiful gardens of Naranjestan, Sheikh Baqli is buried alongside his songs and grandsons.

It is said he had a peculiar childhood where religious visions would often overtake him. At the age of fifteen, with increased visions and dreams, he abandoned his trade of a grocery and left for the desert. Eighteen months later he returned and joined a Sufi school. He would go on to pen the incredible ‘The Unveiling of Secrets’.

I first attempted to find the tomb of Ruzbihan Baqli in 2018, but Allah had ordained that I would find him almost a year later in the spring of 2019. With a dear friend, we came across his tomb without much effort. The low metal gate was locked, but one could still see the modest structure. Around the site were more plants then one could count, but as we were about to depart with our prayers performed, an old man, who was the custodian came and unlocked the door. It was apparent that Sheikh Baqli does not receive many visitors, and my estimation as to why would be that was a Sufi, a Sunni Sufi, whose tomb was forgotten and went into decay for centuries, especially after Iran became a Shiite state under the Safavid who highly discouraged Sufism of this type. In the late 1970s (just before the Islamic revolution) renovation work was done on the shrine, the result of which remains today. It is also worth noting the script written behind the graves with sections painted over (which I have been told had the name of the late Reza Shah, which the Islamic revolution wiped).

Ruzbihan, like his contemporaries, left Shiraz and travelled across the middle east to Iraq, Syria and finally to Makkah and Medina to perform the Hajj. On his return he set up a centre of teaching and for the next fifty years taught and his work remained popular generations after his death.

Within the Islamic tradition, the figure to whom Ruzbihan could be closely compared to is Ibn Arabi, as both men articulated extensive visions and sailed the territory of inner experiences just as the Sufi traditions were beginning to take shape. Today Ruzbihan remains mostly unknown, except in some selected circles in Iran, India, Central Asia and Turkey.

The Garden of 40 Saints

My introduction to the mystics and Sufis of Shiraz was made by a Shirazi friend. Since arriving in Shiraz, I had observed that Shiraz was surrounded by mountains, and if one looked closer with interest, it would be noticeable that on these mountains there are caves, monasteries (that I would learn later are of Sufi orientation) and simple graves. All of these, again I would learn later, belong to Sunni Sufi mystics, that are revered today because of convenience (a few of these are located by the city gate) or are completely ignored.

The garden of 40 saints is a useful example. A fifteen minute walk behind the tomb and gardens of Hafez is a park that even a Shirazi will not know the existence of. A heavy wooden door, above which a fairly recently placed tile work reads the words ‘Sahetman Chehel Maqam’ (The Station of 40 Saints), enter and one might be confused for thinking he is in a government or municipal office, as the sound of phones and everyday speech (although faint) is heard from immediately in front, but no, look to your right and in this crowded garden where trees and plants conceal themselves are the tombs and gravestones that are too numerous to count. I counted and there are indeed exactly forty. The story, as told by a Shiraz, is that these forty saints were all connected by a spiritual chain, and starting from the blessed first, each would be buried by the subsequent, until the last who was buried by an ordinary man and it was here that the chain would break. The stones are in ruins but it appears effort has been made to decorate the inscriptions on some of these, no doubt by investment made by Shirazi religious funds. It is also worth mentioning these fort saints were Sunni, and I would dare to suggest that this is perhaps why such an important site has been neglected and today sees no pilgrims.

My visit took place in the summer, on which the midday sun spared no mercy, so I raised my hands to a cold water fountain and drank enough to last a man a whole day. I did attempt to read Surah Fatiah for each saint, but this traveller lacked the discipline and prayed that Allah would accept it and spread its intention to all the blessed forty buried here.

The Garden of Forty saints is not easy to find, so here is a link to google maps if you want a precise location.

Haft-tanan (The 7 saints in the Stone Museum)

One of the oldest sites in Shiraz, the magnificent gardens and the mansion on the north-side nest the graves of seven saints. There is little to no information available about these saints, except they were mystics and were buried together in this garden that is pre-Zandieh era and dates back to the Karim Khan period (late 18th century). The garden was built around the graves.

The stone museum can be an overlooked sight in Shiraz, but it is a treasure for historians and lovers of stone craftsmanship as well as calligraphers and artists. As one climbs the outer platform of the mansion there are five chambers visible. These document famous Islamic and Persian stories, including that of Prophet Musa, Ibrahim, as well as a lesser known tales of Dervishes from Tabriz. Placed underneath the wall art are stones, columns (some are fragments) and even Mosque Mihrabs. These date back in origin to Pre-Islamic Iran, with the stones re-used from ancient temples and monuments. The calligraphy on the stones is rare in beauty, and such a mixture of styles is almost impossible to find in one place on such surfaces. The styles are Kufic, Thalis, Nastaliq Divan lines, Taqiqi and many more.

The Well of Mortaz Ali

I did not have the opportunity or blessing to visit the maqam of Mortaz Ali, but I will give the account baesd on what I have been told by locals. Allah knows the truth. Mortaza Ali, a dervish, is believed to have been buried on a mountain top overlooking Shiraz. Historians and archaeologists now believe the site of his grave was once a Zoroastrian temple, but after the arrival of Islam, Sufi mystics and pilgrims made this a place of worship and to seek solace.

This is a naturally occurring cave with Safavi era inscription on the entrance, which is almost faded. The entire structure has been re-created and is in excellent condition. The story I have heard details that the well found here formed when a Sufi dervish wept, either out of love for the Beloved, or in agony of his own soul and out of tears, which were plenty and heavy, the earth opened up and a well formed. Another tradition reads that this site was visited by Imam Ali but Allah knows the truth behind this story.

This structure is one of the highest placed in Shiraz and requires moderate strength from the pilgrim to visit. Albeit today it is not a pilgrim who endures the hardship to visit but young men and women who escape the scrutiny of the city below and want solace to entertain themselves with worldly distractions. Allah is the best of guides.

Khawaju Kermani (Kamal Al-din Ali bin Mahmud)

“All that is on earth will perish: But will abide (forever) the Face of thy Lord, – full of Majesty, Bounty and Honor” The Holy and Sacred Quran 55:27

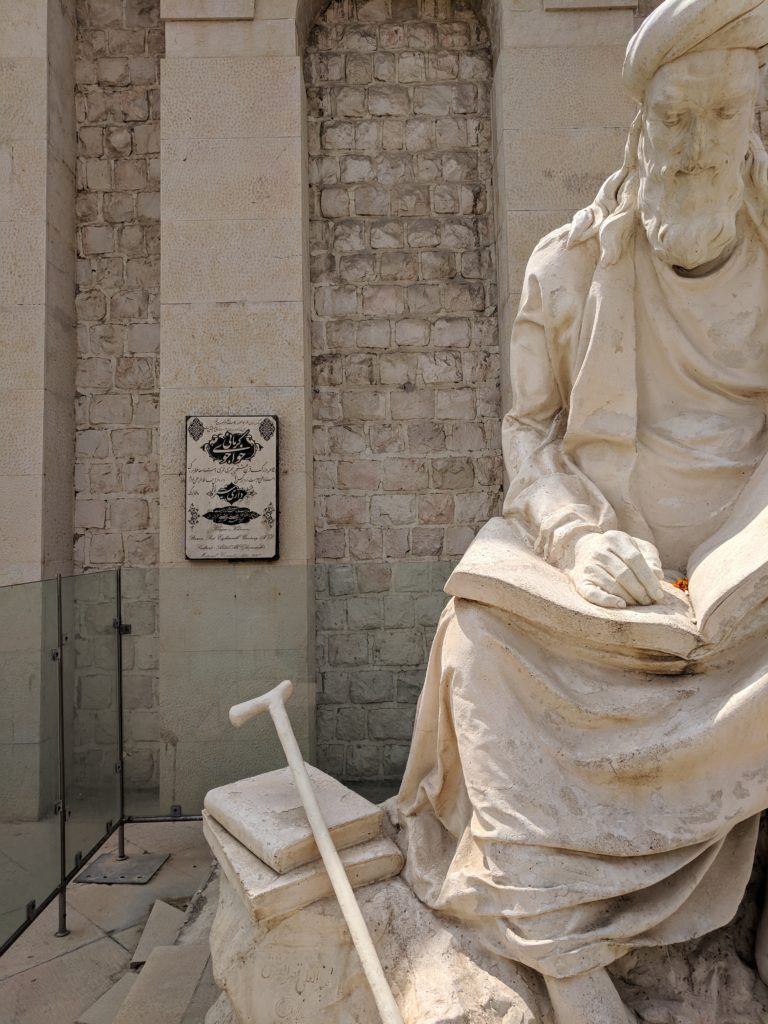

A Sufi saint, Khawaju was born in the city of Kerman and is today buried on this gorge by the city entrance of Quran gate on the foot of the Sabuy mountain. Unroofed, the tomb is enclosed in glass and nearby is a stone statue of the saint.

Khawaju, which is derived from the Persian Khwaja is a poetic penname, but the title itself points to the high social status of his clan, and also indicates his association with the Persian Sufi master Shaykh Abu Eshaq Kazeruni, the founder of the Morshediyya order.

Khawaju was a traveller, and like Saadi, travelled the Muslim lands of Egypt, Syria, Jerusalem and Iraq before perfoming the Hajj. In his own writings, Khawaju claims his purpose to travel was to meet other scholars, poets and thinkers. It is said that he kept the company of many poets in Shiraz, including Hafez and Ubayd Zakani.

On the upper levels of the site, are three caves that are believed to be where Khawaju is said to have prayed and sought retreat. One of these caves is now a souvenir shop, and in the other is the grave of Emad al-din Mahmoud.

Final Words

There are more Saints, Mystics, Dervishes, Scholars, Poets and men and women of God buried in Shiraz.

I found this abandoned tomb at the foot of a hill that led to another Khaneh (dervish monastery). What can one do other than read a prayer, recite a Surah and kiss the marble and walk on.

May God bless and protect Shiraz.

If you would like to visit these sites and more, click on the Google Map link below.