Let’s talk about coffee, and in particular in Europe.

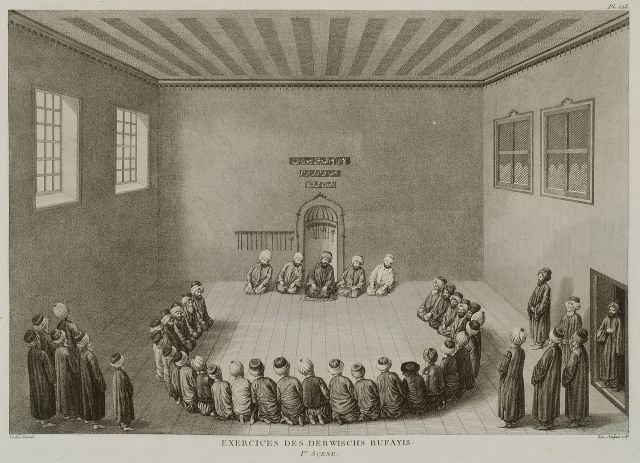

Every time you sip a cup of coffee in London, you are participating in a ritual that stretches back 365 years to a muddy churchyard in the heart of the City of London. But coffee goes way back to the 15th century Yemen where it was found in Sufi shrines. By the 16th century, the drink had reached Persia, Turkey, and North Africa. From there, it spread to Europe and the rest of the world.

The word coffee is derived from the Arabic verb qahyia, “to lack hunger” (reference to the drinks reputation as a appetite suppressant.

Qahwah is the Arabic word for coffee. Every language has merged “Qahwah” into their vocabulary to describe this drink.

Most spoken languages today use the root word ‘Qahwah’ to describe coffee in their local tongue.

The entry of coffee into Europe began soon after the failed Ottoman conquest of Vienna. Its said that a retreating Ottoman army left behind sacks of coffee beans, which the curious Europeans took for camel droppings and then proceeded to burn them. Coffee was discovered and then soon taken into Vienna, and then it made its route into all the European capitals, and eventually landed in Paris and London where it became an instant hit.

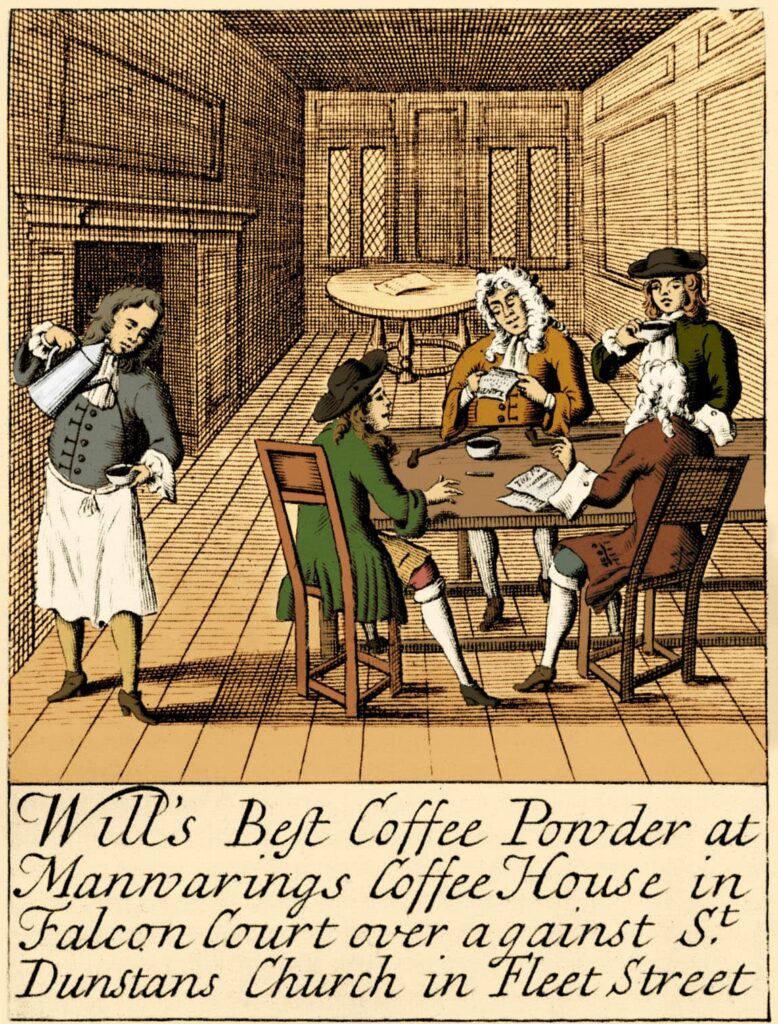

London’s coffee craze began in 1652 when Pasqua Rosée, the Greek servant of a coffee-loving British Levant merchant, opened London’s first coffeehouse (or rather, coffee shack) against the stone wall of St Michael’s churchyard in a labyrinth of alleys off Cornhill. Coffee was a smash hit; within a couple of years, Pasqua was selling over 600 dishes of coffee a day to the horror of the local tavern keepers. For anyone who’s ever tried seventeenth-century style coffee, this can come as something of a shock — unless, that is, you like your brew “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”, as an old Turkish proverb recommends, and shot through with grit.

In early 18th century London boasted more coffee houses than any other city in the western world, except Istanbul.

If you like your flat whites or lattes, you would have struggled with this early form of coffee.

Some described this early Turkish coffee as:

“bitter Mohammedan gruel”

“syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes” while others were reminded of oil, ink, soot, mud, damp and shit.”

But yet, people loved the “bitter Mohammedan gruel”, as it sparked ideas, debate and finally made London sober. Pasqua commented on this social changed and said it “made one fit for business”. Pasqua’s coffee stall a stone throw away from the Royal Exchange, heart of finance in London.

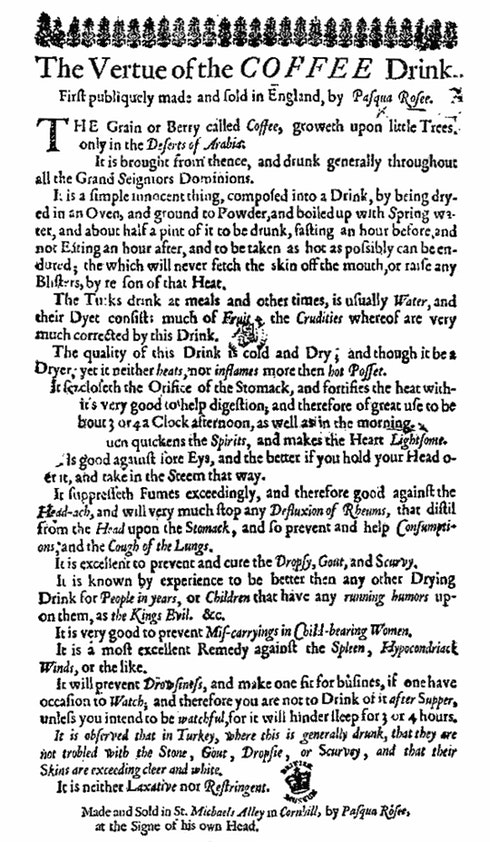

A handbill published in 1652 to promote the launch of Pasqua Rosée’s coffeehouse telling people how to drink coffee and hailing it as the miracle cure for just about every ailment under the sun including dropsy, scurvy, gout, scrofula and even “mis-carryings in childbearing women”

“The Turks drink at meals and other times,…it is good for digestion and therefore of great use to be hour 3 or 4 a Clock afternoon, as well as morning.”

During the mid-17th century, most people in England were slightly or very drunk all the time, mostly due to the fact that London’s water supply was horrid and would make one sick. People then drank watered-down ale, or beer.

The arrival of coffee, then, triggered a dawn of sobriety that laid the foundations for truly spectacular economic growth in the decades that followed as people thought clearly for the first time. The stock exchange, insurance industry, and auctioneering: all burst into life in 17th-century coffeehouses — in Jonathan’s, Lloyd’s, and Garraway’s — spawning the credit, security, and markets that facilitated the dramatic expansion of Britain’s network of global trade in Asia, Africa and America.

Our hero Pasqua was highly successful. By 1656, a second coffee house was opened on Fleet Street, by 1663, 82 had opened up inside the old roman walled city of London.

The term ‘coffee-house politician’ referred to someone who spent all day cultivating pious opinions about matters of high state and sharing them with anyone who’d listen.

However, no respectable women would be found in coffee houses. It wasn’t London before wives became frustrated at the amount of time their husbands spent in the ‘Mohammden Coffee Houses’. In 1674 this frustration erupted into what came to be known as ‘Womens Petition Against Coffee’.

Then came real trouble.

“Charles II, a long-time critic of coffee tried to ban coffee houses all together. Traditionally, informed political debate had been the preserve of the social elite. But in the coffeehouse, it was anyone’s business — that is, anyone who could afford the measly one-penny entrance fee. For the poor and those living on low wages, they were out of reach. But they were affordable for anyone with surplus wealth — the 35 to 40 per cent of London’s 287,500-strong male population who qualified as ‘middle class’ in 1700 — and sometimes reckless or extravagant spenders further down the social pyramid. Charles suspected the coffeehouses were hotbeds of sedition and scandal but in the face of widespread opposition — articulated most forcefully in the coffeehouses themselves — the King was forced to cave in and recognise that as much as he disliked them, coffeehouses were now an intrinsic feature of urban life.”

Pope Clement VIII was asked by his advisers to ban coffee as it was rising in popularity. However, upon tasting coffee, the Pope declared that, “This Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it.” Clement allegedly blessed the bean making it ‘suitable’ for Christians.

Coffee though did not take off right away in Muslim lands either. It faced ban and suspicion in Istanbul, where Sultan Suleiman for apparently two reasons:

1. It was believed to be toxic as per the Qur’anic ban on khamr w’al maysiru (forbidden substance as prohibited in the Qu’ran)

2. The first coffeehouse in Istanbul was in Eminonu (spice bazaar) and it attracted young men especially but also prostitution appeared as a result

Later, after Hurrem Sultan tried the coffee and loved it, and the Sultan had to issue fatwa to allow it. It also had a ban in Makkah around the same time, where some Orthodox Muslims felt it too similarly resembled hashish and wine, and should be banned. Mecca’s chief of police, Kha’ir Beg, decided to go as far as banning the drink, closing down coffeehouses and confiscating and burning coffee. “Coffee drinking continued surreptitiously,” until Beg’s boss, the sultan of Cairo, got wind of the ban and immediately overturned it. It’s said Coffee actually arrived in Istanbul by two Syrian brothers on their adventures.

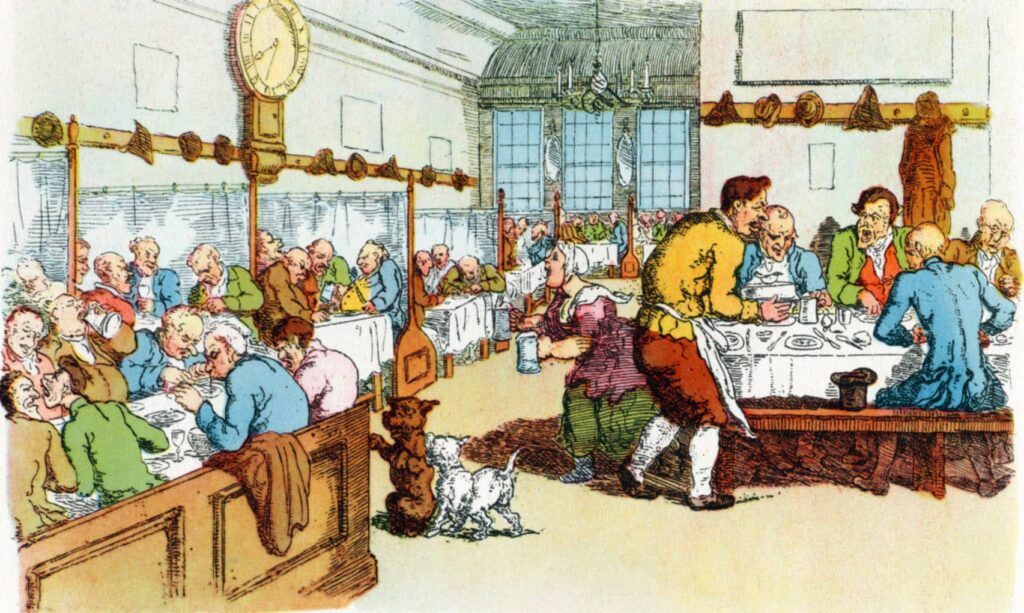

Anyway back to London, it’s said that “By the dawn of the eighteenth century, contemporaries were counting between 1,000 and 8,000 coffeehouses in the capital even if a street survey conducted in 1734 (which excluded unlicensed premises) counted only 551. Even so, Europe had never seen anything like it. Protestant Amsterdam, a rival hub of international trade, could only muster 32 coffeehouses by 1700 and the cluster of coffeehouses in St Mark’s Square in Venice were forbidden from seating more than five customers (presumably to stifle the coalescence of public opinion) whereas North’s, in Cheapside, could happily seat 90 people.”

At their height, Coffeehouses outnumbered pubs in London.

So, what happened inside the coffeehouses?

Nothing happened that would not make its way into conversations in coffeehouses. Unlike today, where strangers would not be caught talking to each other, people loved exchanging conversations:

There’s nothing done in all the world

From Monarch to the Mouse,

But every day or night ‘tis hurled

Into the Coffee-House

As each new customer went in, they’d be assailed by cries of “What news have you?” or more formally, “Your servant, sir, what news from Tripoli?” or, if you were in the Latin Coffeehouse, “Quid Novi!” That coffeehouses functioned as post-boxes for many customers reinforced this news-gathering function.

Based on what was published at the time, coffeehouses were social spaces with no borders where lords sat by fishmongers and where butchers trumped baronets in philosophical debates.

John Macky’s describes a time where noblemen and “private gentlemen” mingling together in the Covent Garden coffeehouses “and talking with the same Freedom, as if they had left their Quality and Degrees of Distance at Home.”

But the coffeehouse’s formula of maximised sociability, critical judgement, and relative sobriety proved a catalyst for creativity and innovation. Coffeehouses encouraged political debate, which paved the way for the expansion of the electorate in the 19th century. The City coffeehouses spawned capitalist innovations that shaped the modern world. Other coffeehouses sparked journalistic innovation.

One of the oldest coffee houses was in Covent Garden, named “Button’s Coffeehouse”, today if you try to locate this you will find in its place a Starbucks. Although coffee has made a comeback, the vanishing opportunities for intellectual engagement and spirited debate with strangers have been quite a trade-off. Today we sit, plugged into our laptops and phones, and find solace in the isolation from the outside world.

As the world becomes even more divided between ‘us’ and ‘them’, i’m increasingly included to remind myself and the world of mutual debt between that the East and the West. The spread of coffee into Europe heralded an era of incredible original thought and inquiry, some academic even argue it was the catalyst for the European Renaissance. It was in coffee houses that intellectuals and the scientist met, that philosophy, itself a byproduct of Greek and Arabic works, was dissected and created the Europe that we have today.