The Basics

The story of the East is written by the West, and no one else must write or document it without their blessing. The global travel photography industry is monoplised by a few Western institutions, and none more prestigious than National Geographic. An American organization founded in 1888, it runs annual photography competitions that are at par with the Oscars, and over the past half-century, National Geographic has created a homogenised standard and feel of ‘travel photography’. The editorial board have chosen, despite repeated criticisms, a practice of rewarding photographers who depict the ‘poor world’ in a way that attracts the attention of its readers and helps shift millions of its printed magazines.

So, what does National Geographic want?

If you’re a photographer who wants to grab the attention of National Geographic and dream of being shortlisted for one of its many competitions, then you must adhere to the following list of unspoken, yet widely practiced, methods of photographing the non-Western hemisphere:

- Travel to any spot in the world, the more remote, the better. For you, no borders exist, no stories too wild, no pain or tragedy too painful. However, if you’re a photographer from certain Eastern countries, you may not enter any of its competitions to show your land. However, a Western photographer can enter your country (as they usually do) and snatch awards by photographing your land and your people. This manipulation of the rules allows certain places to remain less known, maintaining the allure and mystery for a Western audience.

- Know your audience. National Geographic’s audience prefer the unfamiliar and as long as the native is photographed, no boundaries exist. The native can be naked (entirely), in extreme pain (dying or dead) or practicing their religious rituals, but whatever you do, do not show the ordinary. The East is a zoo. Its inhabitants’ beasts and we must at all costs focus on their unfamiliar existence.

- Ethics are optional. If you’re a photojournalist and you want to stretch the truth, do it. If you’re caught, say you’re a ‘visual storyteller’. Consent forms and privacy? Rubbish. The Eastern world is unchartered territory, consent forms aren’t needed.

Creating the ‘Native’

- The native must remain the ‘other’. They key to successfully creating the native is to demonstrate without doubt the stark differences between the native and us. The native found in remote spots of the planet is different in every way. It is through these differences that identities are created, of the native and of us (the Western audience).

‘poor and in suffering’, ‘zealous and colourful’, ‘observable and spectacle’

- To create opposite identities the travel photographer must create the native (an existing or a new). The lens of the camera will be used to identify and exaggerate the natives attributes: race, skin colour, environment, cultural practices, economic and social condition. Any similarities between the native and the photographer are overlooked or wiped, and if a story needs to be told, the photography will also become the writer, social commentator, journalist and/or historian.

- The native is an ‘observable entity’. The native can be observed, tabulated and exhibited. The same way Darwin mapped and organised species, the travel photographer can and must plot the native into a story, a journey, an event. An important exercise that will allow the photographer to claim the natives as his unique own.

- The native is in a state of permanent wait. The native awaits the travel photographer to be finally photographed, his story remains untold. When the outsider enters his home, village or rural society, his voice and life, which had remained inconsequential suddenly take form. And if the native is chosen to be photographed, his story might or might not be heard. The photographer owns not only the photograph but also the story that will be associated with it. Accuracy and integrity are secondary, for what is truly important is that the native is magnificently captured in his strange and bizarre world for a faraway audience.

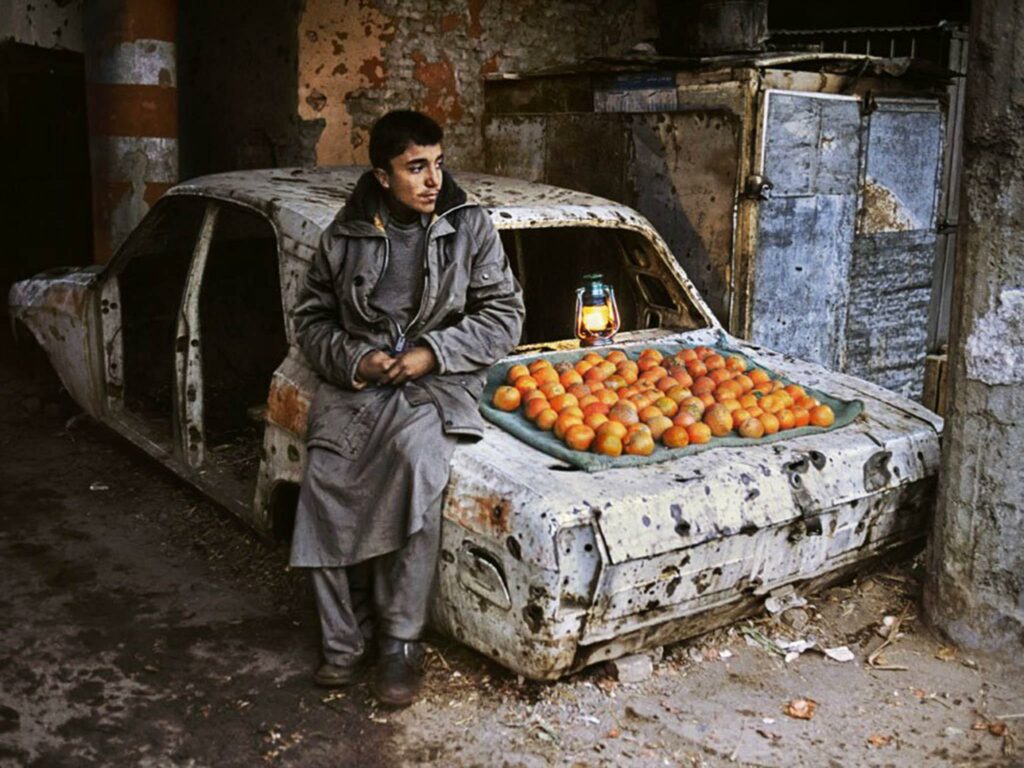

- The native is not an individual. Whether in Kenya or Cambodia, India or Chile, the native resembles any another. Often is hard to tell where the photography is taken, for the location takes backseat to the visual appetite the photographer has prepared for the viewer: the native is dark and naked, exotic and mysterious, either very jubilant or extremely depressed, either the backdrop is the Amazonian jungles, the Ganges or the shoddy and decrepit surroundings in a nameless urban neighborhood.

- The native is always suffering. The old Catholic belief that poverty and disease is a curse for the wretched holds true in photography. The native is either facing a dire famine, or drowning in a flood, either he is unemployed and weak, or overworked and broken, he is either on the move as a nomad, or he in a state of permanent homelessness. In any case, he is helpless and at mercy of those who might care to pay attention. Often the photographer will take it to himself to turn his photography into a ‘awareness campaign’ or to become the self-appointed ambassador for a whole people.

- The native is truly unlike us. The native is rarely shown completing daily rituals that might normalize his existence. The native is usually a nomad, or if stationery, in a mud or straw hut, for organization and society is reserved for the Western people. The native lives exposed to the natural elements; whose existence is as versatile as the natural world.

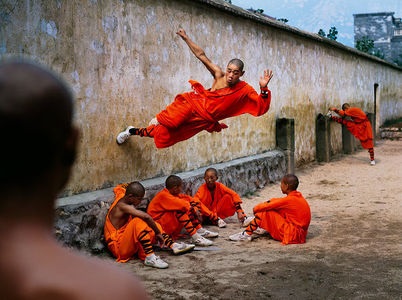

- The native lives in extremes. The native sits on the heavy ends of every measurable scale. He is very religious, his rituals and traditions rich in superstition, his colours a rainbow of mixture, his sounds loud and unfamiliar, his tattoos and piercings unlike anything we know, he is either entirely naked or fully cloaked. To be moderate is not characteristic of the native.

- The native lives a remote life. To be fully immersed into the life and otherly world of the native, we must see them in their natural settings. No urban high-rises, no book shops or cafes or photos of traffic, the native can only be truly captured in their true authentic environment. The Hindu bathes in the Ganges, that is dirty and unsanitary (albeit holy to the naïve native), this is his identity, the Arab rides his camel in sand dunes and is always angry, it’s the only thing he knows, the African is but another animal on the Safari, that’s his natural habitat, the Peruvian hides in the Amazon, for he’s a wild and undiscovered beast. If the native is shown in an urban environment, he is the megalomaniac oil rich Sheikh, or the modern native who yearns to escape his native land for the dreams of rich Europe.

- The native cannot tell his own story and therefore it must be told for him. His illiterate and limited grasp of the world beyond his village and hut disqualifies him from commenting on his condition, and if he wants to he or she can only discuss on a finite set of topics: his poverty, his large family, poor education and infrastructure and his perpetually broken dreams and hopes for a future. Which is clear, from the way the native is photographed, an unlikely reality. Rarely is the native shown to be genuinely smiling, to be a human interacting and living a life with which the outsider can relate.

- The native needs constant re-discovering. The story of the native can be written and re-written, with often the same details, recycled for an audience who might have already forgotten the wretched native from the previous publication. The natives existence is one that, over a century, has yet to be fully exposed, for the native is mysterious and his culture marred in secrecy. Iran, for example, has been ‘de-mystified’, ‘un-veiled’, its ‘hidden secrets’ exposed, it’s ‘cloaked culture’ unhooded. Yet after a century, Iran remains a deliciously unknown fruit that the Western reader loves to bite into whenever the opportunity presents itself.

Why does this all matter?

So what are the real world implications of photographing through the oriental lens:

- Permission is rarely, if ever sought. Although street photography and the question of consent is open for debate, given the nature of outdoor photography, photographers rarely think consent to be integral part of the practice when it comes to photographing portraits or personal spaces. The East is known for its hospitality to guests, especially foreigners, and this kindness is easily exploitable.

- Boundaries do not exist. And if there is one, it does not apply to the Western Photographer. The mysterious happenings behind a door, a curtain or a bedroom wall are to be explored and captured. It’s as if the photographer owes it to himself to shine light on the unknown at any cost, and he will keep crossing boundaries until something dark and alluring will appear, and if nothing is found, photographing the native in his most personal intimate space will do. For example, the photographer Yasmin Mund photographed a set of families asleep on their rooftops. Ms Mund, without seeking and consent, photographed and then had her photo published on multiple global outlets. The photo includes fully and partially naked children and women. Ms Mund’s photo won multiple accolades, including one by National Geographic in 2016. The caption to the original photo was so racially insensitive, it was heavily trimmed after I pushed National Geographic to withdraw the award and remove the photo.

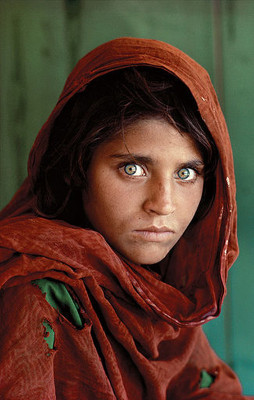

- The narrative to be written. The photograph is often accompanied with a backstory, and it is very difficult to verify the details of what led to the photo to be taken and what exactly is happening in the photo. This is especially true when the person or place being photographed is considered ‘remote’, and names are either not asked or not included in photo essays. Steve McCury’s infamous photo of Sharbat Gula (the ‘Green eyed girl’) is relevant here, as Steve neither had the girls name (it’s doubtful he even asked), nor did he accurately reflect the situation in which the photo was taken. The photo was later accompanied by text that vilified with Russian’s invasion of Afghanistan, implying the intense gaze in the eyes of Sharbat Gula was from the fear of war. Simply not true. This is a common practice in photo journalism and modern storytelling, where one photo will be used to tell a different narrative.

- The natives are all the same. A global non-Western population are categorised into a small subset of buckets. The richness and complexity of people is removed, until an entire continent (e.g. Africa) can be described with a single visual adjective.

- Stereotypes and themes are reinforced. The world today is smaller than it once was, and it is clear we in the wider human family are not all that different despite our incredible diversity. Positioning certain people and societies in a light that reinforces old stereotypes is harmful and creates further divisions. The veil of the conservative ‘Muslim World’ remains a popular visual choice for any photographer in Iran, Iraq and Pakistan when showing women, naked worshippers in the Ganges or Buddhists in their temples are repeatedly shown. Immigrants, climate refugees and victims of drug cartel violence are perhaps the most popular ways South and Central Americans are shown. It’s as if the East, or the native, has not moved on, stuck in their quagmire of superstition and turbulent existence.

- Previous research, imaginings and work done by the native can be discarded or ignored due to their natural irrelevance and inevitable “bias”. The native cannot tell his story, so it must be told for him. This is perhaps the most common and destructive way to re-frame an already framed people and is often delivered by parachuting in Western photographers to cover local events in a country which could easily be captured by native photographers.

At the editorial board level, the same orientalist lens that has proved so profitable is rewarded and celebrated and encourages more of the same behaviour in new photographers. Pain sells, tragedy gets clicks and if a ‘feel good’ story is needed, then a bland story about a non-event in the West is used to deliver that. This recycled approach of covering the ‘native’ and ‘us’ is deeply ingrained in almost every Western newspaper and photography publication.

Further Reading

Challenging Orientalism (Articles, Essays and Podcasts) at Sacred Foosteps

Orientalism by Edward Said

Culture and Imperialism by Edward Said