“Cairo is mother of cities and seat of Pharaoh the tyrant, mistress of broad provinces and fruitful lands, boundless in multitude of buildings, peerless in beauty and splendour, the meeting place of comer and goer, the stopping-place of feeble and strong. Therein is what you will of learned and simple, grace and gay, prudent and foolish, base and noble, of high estate and low estate, unknown and famous; she surges as the waves of the sea with her throngs of folk and can scarce contain them for all the capacity of her situation and sustaining power. Her youth is ever new in spite of length of days, and the star of her horoscope does not move from the mansion of fortune; her conquering capital has subdued the nations, and her kings have grasped the forelocks of both Arab and non-Arab. ”

– Ibn Battuta

Introduction

Cairo, a city of a thousand minarets was once the embodiment of the power of Islam according to the 14th century traveller and observer Ibn Battuta. When Ibn Battuta entered medieval Cairo in 1326, it was under the siege of the black plague (‘Bubonic Plague’ as its known today) killing up to 20,000 people a day. Cairo would be hit by the same plague fifty more times in the next 150 years, a disease that would hurt but never end the glow of this sacred city.

Cairo was founded by the Fatimids (a branch of Shi’ism known as the Ismailis), a caliphate founded in Ifriqiya that spanned the red sea in the east (Egypt to Hejaz) to the Atlantic Ocean in the west (as far as modern-day Algeria) and was present even in the island of Sicily (now part of Italy). Whilst it is easy to shift attention away from the Fatimids when it comes to Cairo, and focus instead on the Mamluks and Ottomans (who arguably not only ruled Cairo longer but have a far deeper legacy in how we view and experience Cairo today), it was the Fatimids, who would go onto establish a place of learning and worship that would impact the religiosity of almost every Sunni Muslim for the next one thousand years through Al-Azhar.

The legacy of Fatimid is found throughout their architecture, where the Shahada, the creed of Islam declaring belief in the oneness of God and Muhammad being the last messenger is extended as per the Shiite theology with the words “and Ali is the Wali (custodian or protector) of Allah”

So, what then is Cairo? Cairo is a city of giants and their high mountains, it is a city of scholars and students and their many scrolls, of Sufis and saints and the hidden caves, of scientists and astronomers and their high gazes, of poets and artists and their paper and stone ceiling vaults, of warriors and slaves and their destiny’s endless brawls. The vibrations that found themselves stirring the air and then the chest of one man in a cave in Makkah had aftershocks that the rest of the world could not prevent. Who raises from dust, a city as grand as Rome, a city as green as Babylon, a city as rich as Khorasan or Isfahan?

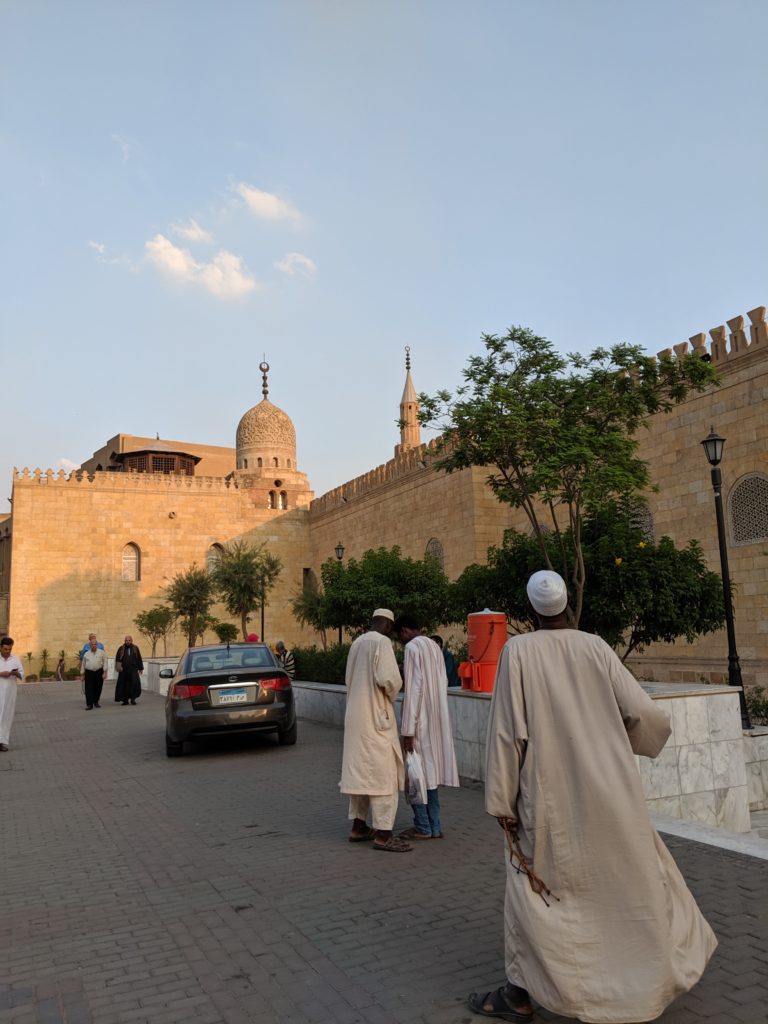

In July 2019 I travelled to Cairo for what would be my third trip, but it might as well have been the first. The medieval city that Ibn Battuta documented seven centuries ago is no more but then it also is. Ibn Battuta entered Cairo during the reign of the early Mamluk’s, slave soldiers who had seized Egypt from the grasp of the Ayyubid’s (the party of Salahuddin the great), and what he must have seen as he entered the walled city could not have been much different to what remains today. Mamluk architecture dominates the old city, although the Ottoman’s ruled for much longer, it is the Mamluk style that remained the style of choice for even the Ottoman rulers, who to their credit, kept the Mamluk design alive (and then ‘borrowed’ the architects to build Istanbul). Other than the Muhammad Ali Pasha mosque (entirely Ottoman in its façade) which rules the skyline over old Cairo, it is the Mamluk architecture language that greets travellers in every other quarter of old Cairo.

I had planned, with the will of Allah, to spend three days in old Cairo with the hope that my brother Omar, who the Almighty has blessed with a thirst for endless knowledge and bestowed with overflowing kindness, would hold my hand and take me through the crowded arteries to the true heart of Cairo. We would focus primarily on Mosques, the older the better, and when possible, visit the graves and mausoleums of the many saints to reflect and recite a prayer.

Omar and I had been in correspondence for a year where we would discuss our thoughts, findings and ideas on many topics, from Islamic architecture to the revival of the Islamic spirit in the world today using creative medias. My heart had been draped by the Persian world for almost three years, after visiting Iran multiple times, but my mind always wondered at the vastly contrasted world of Mamluk Cairo. Cairo was brown, build of stone and sand, Iran was turquoise, built from precious mosaics, Cairo was hard, Iran then seemed poetic and soft. The musings of the Safavid had left me endlessly wondering about the garden and the bird, but Cairo did not bother, it stood vertically and reached into the sky with so many minarets that it could not be ignored. Unable to deny the call any longer, I planned my journey and within days flew to the port of Cairo.

Salar and Sinjir al-Jawly Madrasa and Khanqah

In the next three days, Omar and I would walk 30km, visit almost 50 mosques, climb 5 minarets, see 18 sabil-kuttabs and read Surah Fatiha at 28 mausoleums. There is also another Cairo, downtown and ‘New Cairo’, both we avoided for reasons not worth stating (but if you are curious, downtown is the French and British quarter build during the time of European occupation and New Cairo is miles of sprawling new housing developments). Our path in Old Cairo began with the most depleted sights of all, Salar and Sinjir al-Jawly Madrasa and Khanqah. Walking distance from the Ibn Tulun mosque, this sight is closed for renovation (as most people will say) but there is no renovation. Heavily looted, it is abandoned and covers itself in its own brokenness. With its main doors shut to students and worshippers, it provides an entrance that it unashamedly exposes to the truly curious and mad. One must walk behind this wonder through the maze of streets and then find this view, a secret an old man whispered to us as he saw us in search, “walk this way and you will see a roof to a house, on this take a step, and then another and you are above the mosque”.

As Omar and I stood and stared at this tragic sight, I recall he attempted an apology for his city, his history, and what he felt was neglect by him, but we both felt the heavy symbolism of starting our journey at this spot. These ruins, this stain, this open humiliation – this was our past and this state is but all of our doing. The next 49 mosques we would see in the coming days would eclipse this place with their grandeur and beauty, and deny in many ways, the idea that Islamic Cairo is in ruins, which is true, but I decided immediately this Mosque, Madrassa and looted Mausoleum would remain my favourite.

Omar would later provided me with details of the founders, translated into English from Arabic.

The two amirs that contributed to this mosque were: Seif al-Deen Salar al-Tatari al-Mansuri; and Alaa al-Deen Sanjar ibn Abdullah al-Jawli. They were both amirs in the reign of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun.

Alaa al-Deen was born in Amad, modern day Kurdish province of Turkey, Diyar Bakr. He was purchased by Jawil and was attributed to him. After training, he was promoted to become lieutenant of Mamluks and then again to govern Gaza and be lieutenant of Mamluks in Egypt. After a career of serving under al-Mansur Qalawun and his son, al-Nasir Muhammad, he retired and worked on the sciences of hadith for the rest of his days.

As for Seif al-Deen Salar, he was born in Tatar and was taken prisoner after the Mamluk-Tatar War. He, too, rose through the ranks during the reign of al-Mansur Qalawun and was among the most trusted Mamluks. He served under the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun as well, becoming a powerful vizier for 11 years, and almost overshadowing the sultan. Salar was even nominated to become Sultan but al-Nasir had him arrested and starved to death in his prison cell.

Ibn Tulun

Ibn Tulun, the most celebrated of all Mosques, is the oldest in Cairo and one of the few entirely Fatimid structures left. Though heavily restored in the last few decades, it still carries sign of its patrons and artists. The minaret resembles that of the great mosque of Sammara in Iraq and the horseshoe arches are a reminder that artists from as far as Andalusia worked to build and restore this ancient structure (this occurred at the end of the Muslim rule in Andalusia, which saw majority of Muslims, Jews and even Christians escape to North African and Egypt to guard themselves against European Christian invaders). The minaret of Ibn Tulun is one of the shortest I would climb in Cairo, but just like every other after it, it provides a view of the horizon that reminds one of the richness of Islam in these miles. As we began our descent down the minaret, the call for the afternoon began to be recited first from one mosque, then another and then it seemed a thousand more. Soon we could not separate one sound from another and what might appear as disorderly noise to a foreign ear, was to us a command nested inside another, wrapped and tied to another now hanging above and all around us. I could not help now but laugh and looked at Omar to express my wonder – the minarets that stand silently do so in anticipation for this moment, and now they fulfil their purpose so effectively. The command, ‘come to pray, come to pray’ is heard all over Cairo and now no Muslim can deny their ignorance of their duty. We hurried down and within minutes walked under the stone arch of a small mosque to pray, one that has seen worshippers come five times a day for over five hundred years.

Tarabai al-Sharifi – The tilted dome

The mausoleum of the Mamluk Amir Tarabai al-Sharifi is but another mausoleum, there are many like it, but this is the only one with a tilted dome. The dome, naturally circular, sits on a perfectly square base which then sits at one end of a rectangular base. However, the square base is not sitting symmetrically and falls off the rectangular base – providing a site that is highly unusual but one I find extremely beautiful. Architects in Muslim lands were typically artists and mathematicians, who considered a great range of variables when designing structures. To find this anomaly visible and almost celebrated provides an insight into the patron and the architect. There is no creator more perfect then He.

Mosque-Madrasa of Al-Amir Khair Bak – The floral motif dome

Founded by an Ottoman governor of Egypt, this middle ages complex was built using Circassan (Burji) style architecture. The Burji dynasty was a Circassan Mamluk dynasty (from the North Caucasus, along the shore of the black sea). We were about to walk up to the front of the mosque when Omar suggested we try another approach, what if we climbed an adjacent building to look at the mosque face on? We entered the dark ground floor and found a staircase that took us straight up to the roof. We quickly walked up, one, two, three, four, five and six floors and reached the roof. Standing now above the street we witnessed just where we were. The motif dome and its two, three or was it four minarets that preceded it paraded in front of us. There is no place in old Cairo where climbing a roof offers a dull view.

Aqsunqur Mosque – The Blue Mosque

There are many blue mosques in the world, and you may immediately think of the ones in Istanbul and Tabriz, but Cairo has one too. This is perhaps one of the smallest, and most serene. Located in the Tabbana Quarter between the gates of Bab Zuweila and the citadel of Salahuddin, the mosque is built in Syrian architecture style.

We entered this mosque in a state of absolute exhaustion, we had removed our shoes at the entrance and now walked on hard stones that paved the courtyard, on reaching the front of the mosque we collapsed on the carpet. This mosque Omar would explain, is rare as it houses a small garden right in the centre of the courtyard. Amongst the brown stone and sand of Cairo, trees and plantation offer a sweet delight to the eyes. The Mosque custodian came to shake our hands, offer his salutations and then showed us two mausoleums at the rear of the mosque.

Mahmud al-Kurdi – The chevron domed mosque

In a hurried walk to catch another mosque we would walk past this 624-year-old structure. A closer study needs to be done of the patterns on these stone domes, but this chevron design is one of the earliest and most appealing.

Sultan Al-Ghuri Complex

Amongst my favourite etiquette of worship in Islam are those that combine space for worship and the need for human nourishment (of the mind and body). The Sultan Al-Ghuri complex has a Khanqah, Mausoleum, Sebil-kuttab, Mosque and Madrassa. Sultan Al-Ghuri, although having a reputation for his hardness and cruelty, was a patron of the arts, music and poetry, with especial love for refined architecture.

Al-Ghuri was also attracted to Sufis and pious men, which explains why he built a magnificent Khanqah. A place for Sufi gatherings and music, today it serves a similar purpose with more modern and international concerts and cultural events.

It is worth noticing that the mausoleum structure has no outer dome. The dome was considered unstable and replaced with a flat wooden ceiling sometime in the 19th century. Fortunately, the stone muqarnas remain under the dome and have not been lost.

Al-Ghuri mosque also has a magnificent minaret that we would climb. As one reaches the rooftop of the mosque, the market place below us becomes silent and our nose tells us of another sight – cumin and cloves. Cairo has without doubt changed since the time of Ibn Khaldun, but it has also retained much of its habits. Spices have been brought to and grounded in this market place for centuries, and even today if one walks under the Al-Ghuri complex, or in our case, climbs it, the scent of spices is everywhere. It then is fascinating to think that if a resident of old Cairo time travelled to the year 2019, he or she would have a good idea on where to go for spices, soap, garments and candles.

As we climbed higher into the minaret of Al-Ghuri, leaving the city underneath, we found ourselves on a very narrow platform, with Omar on one side and I on the other, we photographed a horizon of minarets that never seemed to end. Looking south we saw the twin minarets by the famous Bab Zuweila.

At many points during our time together (whether climbing minarets, rooftops, or ruins) Omar and I would worry for each other’s safety, as curiosity turned bravery into foolishness (albeit, Omar is sensible, whilst carelessness is more my trait). Evidence: I shook hands with Omar to make an agreement that if we were to return to the rooftop of Al-Ghauri in the future, we will cross the wooden platform that connects the Khanqah to the mosque above the street and market below. With laughter and absolute disbelief, Omar agreed.

Bab Zuweila

As one enters through the gates of Bab Zuweila, a different era begins. One is greeted by two magnificent Mamluk minarets, they welcome you to al-Muizz street, which at only 0.6 miles long is said to have the greatest concentration of medieval architecture in the Islamic world.

I climbed one of the two minarets at Bab Zuweila (the Al-Muayyed Sheikh Minarets) and stood entirely free, to witness, or to fall a great height, the city of a thousand years and a thousand minarets. At this height, the tangles of the world are resolved, the mind starts to turn words that had fermented for years into sights. I, a modern Muezzin, silent in my place, firm in my hold, looked all around the life and saw it all. Omar was across from me in the opposite minaret, and in his eyes, I too saw a glaze that can only be attributed to a reflection or perhaps a realisation that who we are up here is nothing ordinary. It was as if we had, for a moment, shook the ground and shunned off of us all the shame we were expected to carry as Muslims, as immigrants in the land of the Frank, as if we had dismounted from the caravan of despair and joined one of glory and hope – in both our minds, and I know his for he and I are one in this, we were unbreakable as we cast upon our eyes the mountains of horizons visible and invisible. We knew without calculations that north was Jerusalem, currently lost, that to its east was Damascus and Aleppo, that even further are the valleys of Kashmir and that as far as we went, China still has vibrations from the time of our Prophet (pbuh). As we both turned our necks west we saw the great Mosque of Kairouan, and the sacred city of Fes, we felt and understood that this area was reserve for greatness for eternity, that despite our tragic end from the days of glory, lamps of our saints continue to glow and guide us. Cairo then was our citadel, our watch tower, waiting patiently, yet again for all of us to return to continue what we never finished.

Al-Azhar Mosque

Founded in 970 by the Fatimids, it is one of the oldest universities in the world. Alongside the Quran and Islamic law, it once taught logic, grammar, rhetoric and astronomy. Al-Azhar also holds seven million pages of manuscripts dating back many centuries, and event today its scholars consider disputes on a range of matters submitted to them from across the vast Sunni world. It was, and this is worth noting, a Shiite place of learning and worship, and only after Salahuddin became ruler and set up his Ayyubid dynasty, did it become a Sunni institution that continues till today.

The Jewish philosopher Maimonides (Moses Ben Maimon) delivered lectures on medicine and astronomy here during Salahuddin’s rule.

Sayydina al-Hussein Mosque – The Mosque of Imam Hussein

Across the street from Al-Azhar is the mosque of the Imam Hussein. Although built in the year 1154 (865 years old), it was most recently restored in the 19th century and barely shows its age.

Many believe this mosque is the location of the blessed head of the Prophets grandson – Hussein (upon them both be peace and blessings). Imam Hussein’s head was removed from his body at the battle of Karbala which then ended up being buried at one point in the town of Asqalān in Palestine. It was moved later (the details of which are too much to cover here) to Cairo to protect it from potential disrespect from either the crusaders or other traitorous activity during a time of great disorder.

The Yemeni writer Syedi Hasan bin Asad described the transfer of the head thus in his Risalah manuscript: “When the Raas [head of] al Imam al Hussein was taken out of the casket, in Asqalān, drops of the fresh blood were visible on the Raas al Imam al Hussein and the fragrance of Musk spread all over.”

The messenger of God, peace be upon him, said:

“Hussein is of me, and I’m from him. He who loves Hussein shall be loved by God. Hussein is one of my branches.”

Cairo is a city that has guarded and decorated the Islamic world since its foundation. In the year 1258, the capital of the Abbasid empire, Baghdad, was sacked and burnt by the fire of the east – the hordes of Genghis Khan, the Mongols. Baghdad had been the centre of the Islamic world for over 500 years and within 10 days was reduced to ash, dust and blood. A similar fate was delivered upon every city that the Mongols crossed, and it was only until they met the Kipchak (Turkic) Mamluks from Egypt that conquest and destruction of the Muslim world would end.

Hulagu, the grandson of Genghis Khan, send an envoy to Qutuz, the Mamluk Sultan in Egypt demanding their surrender in the middle of the 13th century.

“From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan. To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords. You should think of what happened to other countries and submit to us. You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people. You cannot escape from the terror of our armies. Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor armies stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe. Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled. Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness of your God and then will kill your children and your old men together. At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.”

Qutuz, no stranger to the language of power, responded by killing the envoys and displaying their heads on Bab Zuweila, one of the gates of Cairo.

The Mongols then attempted to form an alliance with the Crusaders, but even they saw this as an unwise choice and opted out (the savagery of the Mongols was well known). The Mamluks and Mongols would go on to fight at the Battle of Ayn Jalut (the “Spring of Goliath”) in 1260, Qutuz, seeing inevitable victory of his forces, marched in fiercely with his helmet removed (to allow his troops to recognise their Sultan to boost moral) yelling the words “wa islamah!” (“Oh my Islam”). This would be the first time the Mongols would face defeat at the hands of an enemy in their entire history and would lead to their eventual dissemination. Some Mongols would settle in their conquered Muslim lands, themselves becoming Muslim (see Berke Khan and the Ilkhante dynasty).

It is an incredible feeling to say that 759 years later I would sit on the footsteps of a Fatimid mosque outside the entrance to Bab Zuweila (who themselves have stood for 1,092 years) staring up at the gates where the heads of the Mongol hung (and they would not be the last). An invitation to war that would change the future of the entire Muslim world. Also near us, as Omar informed me, is the market place where for over 500 years, the Kiswah (the black cloth that covers the Kaabah) was manufactured and sent to the city of Makkah by a convey that would leave Cairo on a camel. A tradition the Ottomans continued once they became the rulers of Egypt.

Cairo is city of immense history and deeply buried richness. It is here where Salahuddin saw his destiny, it was here that the cauldron of every empire would begin or ends its flame. It is here that from the hardest of stones, and from the softest of sands, man would turn himself into Kings and Caliphs for every people and time. It is here that the entire world would unite to witness the glory of Islam even when the capitals of the Caliphate would change, it is this place that would cause Napoleon to lose sleep (he did conquer briefly, but for only three years), it is this place that that at the end of each rule, era, tragedy, success, folds itself the crumbs and beads of the past and crystallise their legacy for all of time and then asks us to give it more

Ibn Khaldun and Cairo

“I saw the civilization of the world and the garden of the earth; the place where different nations gather and the most enlightened people congregate; the iwan of Islam and the seat of power, where the palaces and iwans flourish; where the khanqaahs, madrasas, and youth bloom in every horizon; and the people of knowledge illuminate it like moons and planets.” — Ibn Khaldun

It was in the walls of Al-Azhar that Ibn Khaldun taught and it is now in Cairo that he sleeps. The exact location of his grave is not known, some say it was destroyed to make room for a road in the 1950s but the most accurate information available indicates he rests just outside the city gate of Bab an-Nasr, a five-minute walk. I began my journey in London two days earlier with the hope that I would meet Ibn Khaldun and recite for him a prayer, and for my own self, be in the presence, even if of bones, to a Muslim from a time and a land that exemplified the true power of Islam. Eight years earlier I had visited the town of Seville in Andalusia (now Spain), where Ibn Khaldun spent the largest part of his life, where he lived and served the courts of the Andalusian rulers, where he would create some of the most significant works not only of his life, but that of the entire Muslim world. Ibn Khaldun, in the line of great polymaths, is recognised universally (though many attempt to side line him in preference to European thinkers) as the first true historian and economist (amongst many other titles). His most famous contribution is known as the Muqqadimah (which he wrote in a span of only five months). Earlier this year I was in the city of Tunis, and to my surprise, though He had willed it, I lodged at a house that was nested between Ibn Khaldun’s place of birth and the madrassa he had begun his academic and religious life. Ibn Khaldun’s life was atypical of an extraordinary Muslim in the 13th century, traveling to where the light shone brightest, teaching to those who most sought, dispending knowledge to those most hungry. As Seville, one of the last lands remaining in Muslim hands fell to the Christians, he left for Morocco and returned to Tunis before leaving again for Cairo, where he spent his final years.

I found Ibn Khaldun outside the walls of old Cairo. There are no markers or signs, no stone or marble mausoleums, nothing. Omar and I walked on a dirt path passing people who, sat outside their houses, laughed and talked, smoked and drank tea. Unaware, or perhaps fully aware but unbothered by, the graves of a thousand or more, but these people like many of the poorest in Cairo live amongst one of the many cities of the dead that surround Cairo. It is here amongst the dead that the living found refuge and built their life. Omar once remarked of the Egyptian and his obsession with the dead. I contemplated this quickly and agreed that there is something to be said about the familiarity and nearness that Egyptians have had with those long gone.

Final Thoughts

Cairo is subtle but entirely dominant. No dynasty has resisted its attraction, no ruler could pass it by, no force or person can enter and leave without complete submission. Cairo is a city of closed caverns, where the foot must lead the heart, for the heart cannot understand until the foot has already stumbled. The heart then, is receptive to the language of Cairo, the beauty found in stained glass windows softly drapes the eyes whilst the hardness of the stones prepares one to understand that this is no place to rest endlessly, but one where only perpetual prostration will bend the stubborn marble floors. How beautiful then is the net cast by Cairo for one to weave in and out of?

One must now contemplate further the strength of the arches to understand his own weakness, follow the Iwans with their eyes to find but fail to identify the imperfections, for there are none, to count the thousand glass lamps but then start again, kiss the marble Mihrabs and listen out for the thousand voices that have spent a thousand years reciting His name into the enclave, and the wooden Minbars, man’s attempt to understand His throne by creating a straw structure. Furthermore, let me say this, I have stood under the dome of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque (in Isfahan), arguably the most beautiful in existence, I too have climbed the minarets of the grand Shah Mosque to stare at Naqs-e-Jahan from the eyes of a Safavid, I have also grappled with the fragments of the Blue Mosque in Tabriz, I have also been reduced to a mere speck of dust by the Nasr ol Molk in Shiraz and finally I have prostrated without hesitation, repeatedly, in Mashhad, but none of these defeats were preparation. What to say, how does one armour a human chest of bones and tissue, of muscle and blood, from splitting when the light of our glory, so heavily condensed in this old city, penetrates constantly, in lower frequency until you are but repeating His name. The land of Musa and Yusuf, the city of the broken and the hopeful, the sanctuary of the prosecuted and the seat of the power, the graveyard of the sinful and the nest for the rest of us, the flocks that followed a tune hummed by the Frank, the curious that then return because what else do we do but return home – to our al-Qahira.

In Cairo is the history and detail of our past. In the old city are the houses with keys in the door left behind, here are the libraries with no custodians to guide, here are the limps unlit and prayer rugs covered in dust, all waiting for its children to return and ask the same questions as those before us, the Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk and Ottoman have done their duty – out of an immaterial love they created the city that became the mother of the Muslims. This is no Medina but within the chambers of the saints, flows the blood of greatness that turn even the mud and sand structures into a garden of enormous beauty.

Come, come, come to Cairo and bring with you your questions and then ask this city of a thousand minaret for answers, for “He who has not seen Cairo, does not know the power of Islam” – Ibn Khaldun.

Note: Copyright to all photos is owned by Zirrar.